Internet’s Founding Architects: Latest U.S. Senate Effort To Block Online Pirates Will Instigate Internet Chaos

SAN FRANCISCO, November 18th, 2010 — The U.S. Senate’s latest battle plan against intellectual property piracy online could gain traction and be approved by the body’s Judiciary Committee Thursday, but a large group of the internet’s founding architects are warning that the plan’s technical approach

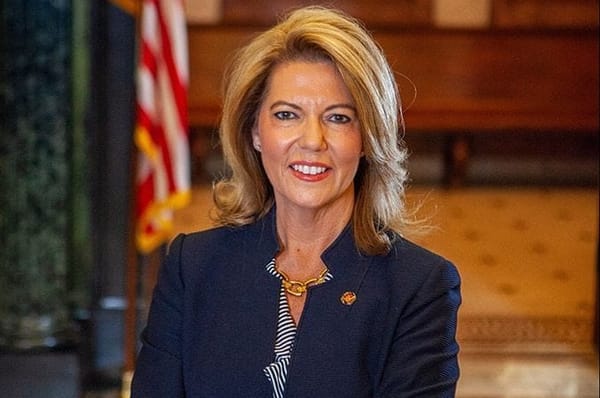

MIT Professor David P. Reed is one of the 89 internet pioneers who told the U.S. Senate Judiciary Committee Tuesday that a Hollywood-championed bill targeting online pirates is fatally flawed. The committee could vote to approve the legislation on Thursday. Photo by Joi Ito.

SAN FRANCISCO, November 18th, 2010 — The U.S. Senate’s latest battle plan against intellectual property piracy online could gain traction and be approved by the body’s Judiciary Committee Thursday, but a large group of the internet’s founding architects are warning that the plan’s technical approach would wreak havoc and destabilize the global network.

The group includes many of the pioneering engineers who designed the fundamental protocols and standards that gave birth to the internet and the web, and which makes up its DNA today.

The group of 89 network engineers and internet visionaries sent a dramatically-worded letter to all of the Senate Judiciary members on Tuesday warning that the Combating Online Infringement and Counterfeits Act would cause chaos because people would simply set up alternative ways to look up domain names “outside the control of U.S. service providers, but easily used by American citizens.”

“Errors and divergences will appear between these new services and the current global [domain name system,] and contradictory addresses will confuse browsers and frustrate the people using them,” they added. “These problems will be widespread and will affect sites other than those blacklisted by the American government.”

The bill is question is sponsored by Senate Judiciary Committee Chairman Patrick Leahy, but it enjoys bipartisan support of 17 other senators.

Among other things, its goal is to enable the Justice Department to expedite the process of ordering registries and registrars to block access to domain names of web sites that the U.S. attorney general deems are dedicated to piracy.

The bill would also enable Justice to use the court order against enabling third parties, such as internet service providers, payment processors and online ad networks. The list of blocked sites would also be posted online by the White House intellectual property czar.

Leahy, a strong, long-time advocate of the entertainment industry, and no technophobe himself, first introduced the bill in late September. So far there’s been no hearing to air the concerns voiced by the internet community.

The Vermont Democrat said upon the bill’s introduction that it would provide Justice with an important new tool, but he didn’t explain what exactly it would do. Justice has already launched successful domain name blocking campaigns against pirate web sites.

The engineers’ Tuesday letter reflects a growing schism between themselves and other advocates of the open internet and other powerful members of the internet community whose industries are being dramatically reshaped by both digital technology and unfettered global piracy.

The engineers’ ethos of openness is a fundamental design principle packed into the protocols of the internet. But the ethos baked into the software code of the global internet infrastructure is having a hard time accommodating the needs of the rest of the world that’s taken shape online, creating the long-standing debates over how the global network should be managed. Those debates have manifested themselves through the net-neutrality debate and constant and ongoing debates in legislatures across the world over the nature and extent of individuals’ anonymity, the role of intermediaries, and how illegal behavior should be tracked online.

In the United States, the technology and entertainment communities, such as in this case, usually talk past one another and don’t squarely address each others’ concerns.

For example, in addition to the potential chaos of the senate bill’s current approach, the engineers have also voiced a concern about censorship, giving short shrift to the idea that blocking content could be limited to blatantly illegal activities.

For its part, the Motion Picture Association of America’s interim chief Bob Pisano on Tuesday wrote an editorial in The Hill that emphasized the destructive nature of online piracy. But he didn’t address the technical aspects of the current legislation under consideration, and why it would improve law enforcement authorities’ enforcement powers dramatically enough to justify risking the destabilizing the internet’s addressing system.