A Short History of Online Free Speech, Part I: The Communications Decency Act Is Born

WASHINGTON, August 19, 2019 — Despite all the sturm und drang surrounding Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act today, the measure was largely ignored when first passed into law 23 years ago. A great deal of today’s discussion ignores the statute’s unique history and purposes as part of the

WASHINGTON, August 19, 2019 — Despite all the sturm und drang surrounding Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act today, the measure was largely ignored when first passed into law 23 years ago. A great deal of today’s discussion ignores the statute’s unique history and purposes as part of the short-lived CDA.

In this four-part series, Broadband Breakfast reviews the past with an eye toward current controversies and the future of online free speech.

This article looks at content moderation on early online services, and how that fueled concern about indecency in general. On Tuesday, we’ll look at how Section 230 is similar to and different from America’s First Amendment legacy.

On Wednesday, in Part III, Broadband Breakfast revisits the reality and continuing mythology surrounding the “Fairness Doctrine.” Does it or has it ever applied online? And finally, on Thursday, we’ll envision what the future holds for the legal treatment of “hate speech.”

While most early chat boards did not moderate, Prodigy did — to its peril

The early days of the internet were dominated by online service providers such as America Online, Delphi, CompuServe and Prodigy. CompuServe did not engage in any form of content moderation, whereas Prodigy positioned itself as a family-friendly alternative by enforcing content guidelines and screening offensive language.

It didn’t take long for both platforms to be sued for defamation. In the 1991 case Cubby v. CompuServe, the federal district court in New York ruled that CompuServe could not be held liable for third party content of which it had no knowledge, similar to a newsstand or library.

But in 1995, the New York supreme court ruled in Stratton Oakmont v. Prodigy that the latter platform had taken on liability for all posts simply by attempting to moderate some, constituting editorial control.

“That such control is not complete…does not minimize or eviscerate the simple fact that Prodigy has uniquely arrogated to itself the role of determining what is proper for its members to post and read on its bulletin boards,” the court wrote.

Prodigy had more than two million subscribers, and they collectively generated 60,000 new postings per day, far more than the platform could review on an individual basis. The decision gave them no choice but to either do that or forgo content moderation altogether.

Many early supporters of the internet criticized the ruling from a business perspective, warning that penalizing online platforms for attempting to moderate content would incentivize the option of not moderating at all. The resulting platforms would be less useable, and by extension, less successful.

The mid-1990s seemed to bring a cultural crises of online indecency

But an emerging cultural crisis also drove criticism of the Stratton Oakmont court’s decision. As a myriad of diverse content was suddenly becoming available to anyone with computer access, parents and lawmakers were becoming panicked about the new accessibility of indecent and pornographic material, especially to minors.

A Time Magazine cover from just two months after the decision depicted a child with bulging eyes and dropped jaw, illuminated by the ghastly light of a computer screen. Underneath a bold title reading “cyberporn” in all caps, an ominous headline declared the problem to be “pervasive and wild.”

And then it posed the question that was weighing heavily on certain members of Congress: “Can we protect our kids — and free speech?”

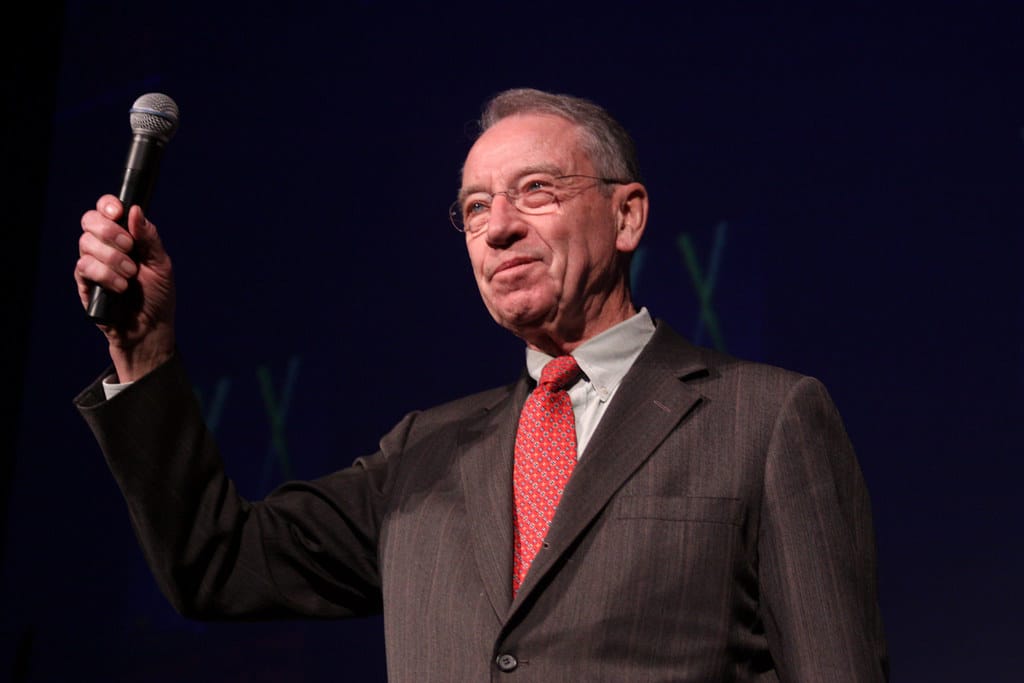

The foreboding study behind the cover story, which was entered into the congressional record by Sen. Chuck Grassley, R-Iowa, was found to be deeply flawed and Time quickly backpedaled. But the societal panic over the growing accessibility of cyberporn continued.

Thus was born the Communications Decency Act, meant to address what Harvard Law Professor Howard Zittrain called a “change in reality.” The law made it illegal to knowingly display or transmit obscene or indecent content online if such content would be accessible by minors.

Challenges in keeping up with the sheer volume of indecent content online

However, some members of Congress felt that government enforcement would not be able to keep up with the sheer volume of indecent content being generated online, rendering private sector participation necessary.

This prompted Reps. Ron Wyden, D-Ore., and Chris Cox, R-Calif., to introduce an amendment to the CDA ensuring that providers of an interactive computer service would not be held liable for third-party content, thus allowing them to moderate with impunity.

Section 230 — unlike what certain politicians have claimed in recent months — held no promise of neutrality. It was simply meant to protect online Good Samaritans trying to screen offensive material from a society with deep concerns about the internet’s potential impact on morality.

“We want to encourage people like Prodigy, like CompuServe, like America Online, like the new Microsoft network, to do everything possible for us, the customer, to help us control, at the portals of our computer, at the front door of our house, what comes in and what our children see,” Cox told his fellow representatives.

“Not even a federal internet censorship army would give our government the power to keep offensive material out of the hands of children who use the new interactive media,” Wyden said. Such a futile effort would “make the Keystone Cops look like crackerjack crime-fighters,” he added, referencing comedically incompetent characters from an early 1900s comedy.

The amendment was met with bipartisan approval on the House floor and passed in a 420–4 vote. The underlying Communications Decency Act was much more controversial. Still, it was signed into law with the Telecommunications Act of 1996.

Although indecency on radio and TV broadcasts have long been subject to regulation by the Federal Communications Commission, the CDA was seen as an assault on the robust world of free speech that was emerging on the global internet.

Passage of the CDA as part of the Telecom Act was met with online outrage.

The following 48 hours saw thousands of websites turn their background color to black in protest as tech companies and activist organizations joined in angry opposition to the new law.

Critics argued that not only were the terms “indecent” and “patently offensive” ambiguous, it was not technologically or economically feasible for online platforms and businesses to screen out minors.

The American Civil Liberties Union filed suit against the law, and other civil liberties organizations and technology industry groups joined in to protest.

“By imposing a censorship scheme unprecedented in any medium, the CDA would threaten what one lower court judge called the ‘never-ending world-wide conversation’ on the Internet,” said Ann Beeson, ACLU national staff attorney, in 1997.

By June of 1997, the Supreme Court had struck down the anti-indecency provisions of the CDA. But legally severed from the rest of the act, Section 230 survived.

Section I: The Communications Decency Act is Born

Section II: How Section 230 Builds on and Supplements the First Amendment

Section III: What Does the Fairness Doctrine Have to Do With the Internet?

Section IV: As Hate Speech Proliferates Online, Critics Want to See and Control Social Media’s Algorithms