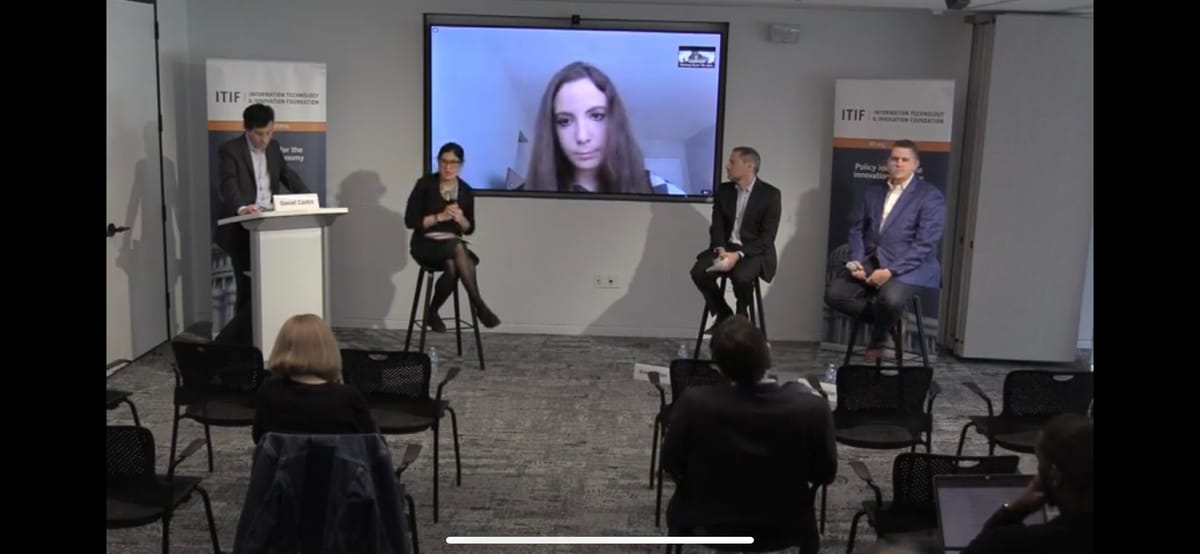

Panelist at Information Technology and Innovation Foundation Event Say Deepfakes Are a Double-Edged Sword

WASHINGTON, March 23, 2020 – “Democracies will be at a disadvantage” if deepfakes become common, Emerging Technologies Fellow Lindsay Gorman told panelists gathered online, on March 12 at the Information Technology Innovation Foundation. Surprisingly, while deepfakes present an extraordinary, fast-m

Adrienne Patton

WASHINGTON, March 23, 2020 – “Democracies will be at a disadvantage” if deepfakes become common, Emerging Technologies Fellow Lindsay Gorman told panelists gathered online, on March 12 at the Information Technology Innovation Foundation.

Surprisingly, while deepfakes present an extraordinary, fast-moving challenge, deepfakes can be used for good as well.

Gorman argued that because democracies rely on facts and trust in government figures who can communicate directly with the people, deepfakes can erode this system.

Deepfakes are altered “synthetic media” that can take several forms: fake videos, images, comments, texts, audio, etc.

Gorman said there has been an “explosion of cheapfakes” in the political realm. When there is a “technical manipulation” it would be helpful to clearly label it rather than take it down and enter into the discourse of constitutional rights, said Gorman.

Pornographic videos are the most common deepfakes, but the conversation seems to swirl around misinformation, said ITIF Vice President Daniel Castro.

Several universities are working to “help communities in detection” because these technologies are varied and diverse, said Facebook Cybersecurity Policy Lead Saleela Salahuddin. “The speed of detection is critical,” said Salahuddin.

Salahuddin said users have to be cautious because the “adversary will pivot to find some loophole” in your protections and detection.

The audio aspect creates a great threat because the technology can learn the speaker’s voice and regurgitate scripted lines, said Ben Sheffner, vice president and associate general counsel for Motion Picture Association.

Salahuddin said a financial institution Facebook works with was concerned about what deepfake audio could mean for accessing financial information and accounts. Salahuddin suggested that while deepfakes are spreading wildly, this speed could be a catalyst for “growth and resilience.”

“Detection is crucial,” said Gorman. But regarding misinformation, instead of solely being distrustful of everything users see, there is a need to find factual and trustworthy sources of information, Gorman said.

Not trusting anything is an “authoritarian model,” warned Gorman.

Congressional fever to legislate regarding deepfakes can be “tempered” by recognizing that there are laws that already protect users from a lot of the harms that are inflicted by deepfakes, said Sheffner.

But the first amendment makes it challenging to regulate even “false speech,” Sheffner said.

Michael Clauser, head of data and trust at Access Partnership, doesn’t think deepfakes are all bad—a position he came to over time. While working with a technologist, Clauser learned that the “underlying technology” of deepfakes can be used to solve issues by orchestrating and training algorithms when they are missing data.

For example, deepfakes can train artificial intelligence to recognize cancer in diagnostic tests.

Clauser said “draconian laws” for deepfakes would actually be more damaging for the United States than helpful.

Member discussion