Lawmakers, Prosecutors and Big Tech Companies Spar at Senate Hearing Over Unlocking Encryption

WASHINGTON, December 11, 2019 – Lawmakers remain concerned about law enforcement’s inability to access highly encrypted devices for investigations. Tuesday’s Senate Judiciary Committee hearing questioned some representatives from big tech on the matter. This isn’t going to be a world where social me

Masha Abarinova

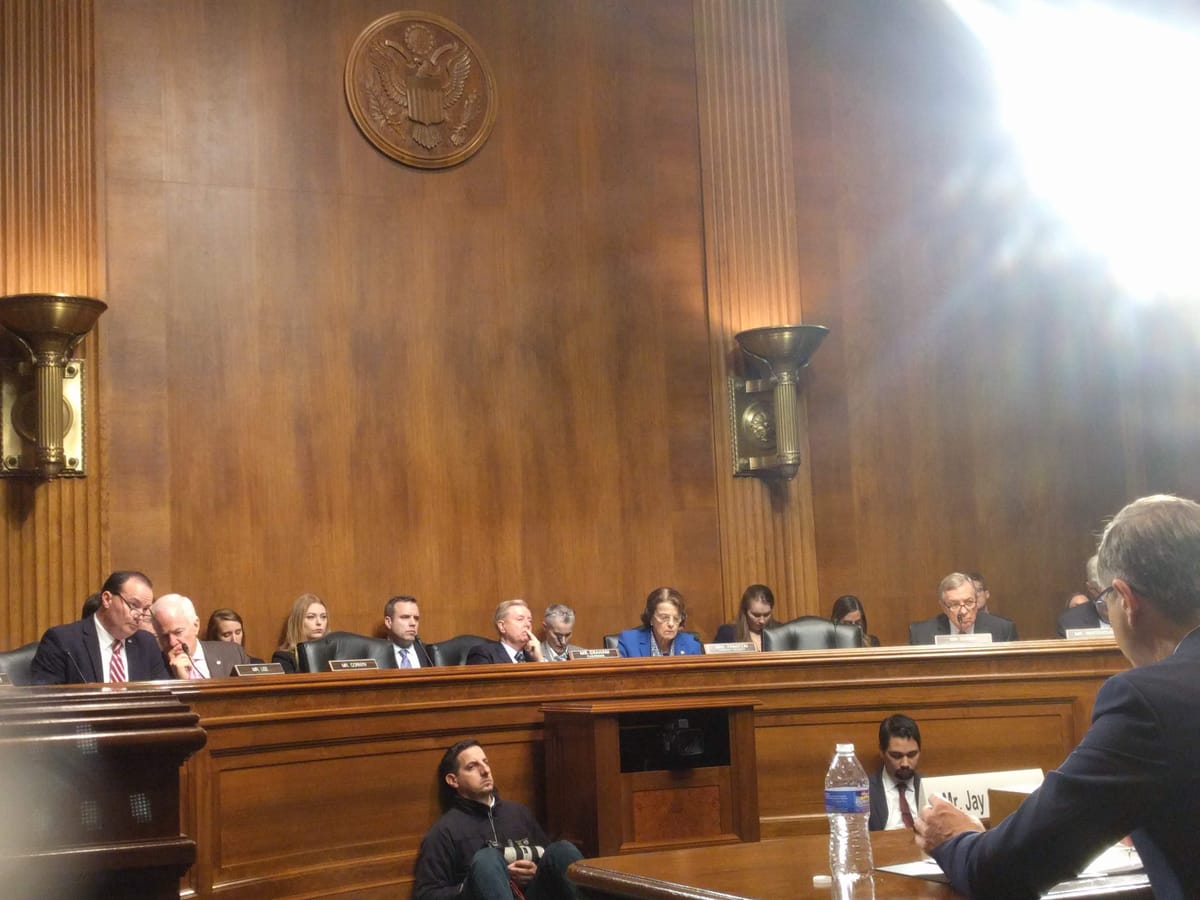

WASHINGTON, December 11, 2019 – Lawmakers remain concerned about law enforcement’s inability to access highly encrypted devices for investigations. Tuesday’s Senate Judiciary Committee hearing questioned some representatives from big tech on the matter.

This isn’t going to be a world where social media is a haven for child abusers and other criminals, said Committee Chairman Lindsey Graham, R-S.C. Big tech can be either the problem or the solution to this dilemma, but they need to take action on encryption. Otherwise, Graham said, these companies face repercussions from Congress.

When a crime is committed, said Ranking Member Dianne Feinstein, D-Calif., it is imperative that these devices be opened. The tech industry has a responsibility to respond to law enforcement’s concerns, she said, and that determines the degree of congressional action.

Sen. Dick Durbin, D-Ill., inquired about how encrypted information is affected under the Children’s Online Privacy Protection Act. Obtaining this information is not only about deterring hackers or foreign actors, he said, but it is about the government protecting children.

Because of Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act, said Sen. Richard Blumenthal, D-Conn., big tech uniquely enjoys immunity from legal action. Sen. Sheldon Whitehouse, D-R.I., added that these companies seem to profit off encryption, yet they are unwilling to take responsibility for the negative effects they might incur.

Representatives from tech companies included Erik Neuenschwander, manager of user privacy at Apple, and Jay Sullivan, product management director for privacy and integrity at Facebook’s Messenger. They emphasized that their respective companies are actively working to ensure safety and security across devices.

Encryption is one of the most important mechanisms a nation has in order to safeguard an increasingly interconnected future, Neuenschwander said. Currently, Apple doesn’t have the ability to retrieve encrypted information off a device. However, he said, that means malicious actors also do not have access to that personal data.

Neuenschwander also added that Apple works closely with law enforcement and government agencies, receiving thousands of requests. Apple’s team has also trained law enforcement officers in the U.S. and around the world on its security processes.

Most Facebook’s methods to combat malicious actors, Sullivan said, are behavioral and based off social interaction. Facebook does not sell or share minors’ data to third parties, and Facebook does not use private messages for targeted ads or other algorithms, he said.

End-to-end encryption is the best technology available to make messages safe and secure, Sullivan continued. If the United States rolls back its support for privacy and encryption, foreign application providers will fill that vacuum to provide the privacy and security that people demand.

Tech companies have no external incentive to mandate the regulation of encrypted devices, said Prof. Matt Tait, cyber security fellow at the Lyndon B. Johnson School of Public Affairs. Encryption hinders law enforcement in three ways: device searches, which are impacted by a user passcode, traditional wiretaps, which are impacted by end-to-end communications and cyber tips, where companies can alert law enforcement of known child abuse material.

Options exist for conducting wiretaps and retaining cyber tips without altering encryption, Tait said. Only device encryption is amenable to a “front door” access mechanism.

New York City District Attorney Cyrus Vance was also on the panel, and he reiterated that law enforcement has lost functionality due to encrypted devices.

Apple and Google have engineered their phones to no longer have the capacity to be unlocked without encryption, he said. Vance said officers can only access about half of the encrypted phones that come into the DA’s office.

Encrypted material should not go beyond the law when a judge signs a search warrant, Vance said. For their own private business interests, the Fourth Amendment grants a right to not only privacy but to anonymity.

Vance emphasized that law enforcement officials having access to the cloud is not a suitable substitute for lawful access to a device. The cloud only stores data that has been saved. Moreover, a user can opt not to backup particular data to the cloud. The device itself, he said, contains the most critical evidence.

Member discussion