Sean Gonsalves: After Years of Talk, Cambridge is Now Taking Serious Look at Municipal Broadband

Cambridge aims to construct a citywide fiber network that passes all 52,300 residences and businesses in the city.

Sean Gonsalves

In Cambridge, Massachusetts, digital equity advocates and city leaders have been debating the idea of building a citywide municipal fiber network for years now, mostly over whether the estimated $150 to $200 million it would cost to build the network would be worth it.

In a tech-savvy city, home to Harvard and MIT, the former city manager was resistant to a serious inquiry into municipal broadband. He retired last summer. But before he left, he relented on the broadband question – under pressure from city councilors and a local citizen group advocating for municipal broadband, Upgrade Cambridge.

With many residents weary of being held hostage to the whims and high cost of service from the monopoly provider in town (Comcast), which currently controls 80 percent of the city’s market, in 2021 the city hired the well-regarded Maryland-based consulting firm CTC Technology & Energy to conduct a thorough feasibility study. Now, with a new supportive city manager in office, city leaders have agreed to continue to investigate the options laid out in the recently published study.

‘Significant public support’ even if it requires tax money

The study found that for Cambridge to construct a “financially sustainable” citywide fiber network that passes all 52,300 residences and businesses in the city, “a significant public contribution would be required.”

“In a base-case scenario that applies conservative construction cost assumptions and reasonable revenue projections,” the study says, “the network could require an upfront public capital contribution of $150 million.”

While some city leaders initially balked at the price tag, a market survey conducted by CTC, found “significant public support for the City taking steps to bring about a new FTTP service, even if a public contribution is required.”

“Eighty-seven percent of respondents agreed that Cambridge needs an additional Internet service provider. When asked if they support City facilitation even if it required a contribution, two-thirds of respondents strongly agreed (40 percent) or agreed (26 percent) the City should facilitate building a fiber broadband network that allows for high-speed service and competition, even if this requires a tax subsidy.”

And when asked if they would be willing to purchase services from a new provider, 58 percent of survey respondents who now get service from Comcast said they would be “very or extremely likely” to subscribe to new Internet service.

Early on, the study seeks to disabuse councilors of the notion that municipal broadband means the city must go it alone and “be the only entity that builds, operates, maintains, and directly markets and offers retail services.”

The city has options, which may involve public-private partnerships. In fact, the study says, “there exists a strong likelihood of private interest in a partnership with the City on a broadband network.”

From there, the study lays out four models the city could pursue and includes a detailed analysis of the risks and trade-offs associated with each: a network fully owned and operated by the city; one where the city builds and owns the infrastructure and then contracts with a private ISP to offer retail service; an open access network in which the city builds and owns the infrastructure and then leases the network to multiple private providers; or one that is largely funded and operated by a private provider.

Cost assumptions and architecture

The construction cost estimates were based on several assumptions, namely that the network would consist of “62 percent aerial construction using existing utility poles and 38 percent underground construction” with an estimated construction timeline of about five years.

Additionally, the cost estimate assumes a 40 percent take-rate that would generate $70 per month, per user “with prices increasing by 3 percent per year.”

As for network architecture, the study advises the city seek to build a network “based on a Gigabit Passive Optical Network (GPON) architecture, which is the most commonly provisioned fiber-to-the-premises service” – the same kind of architecture used by the AT&T, Verizon Fios and Google Fiber, which could be “easily leveraged by triple-play carriers for voice, video, and data services.”

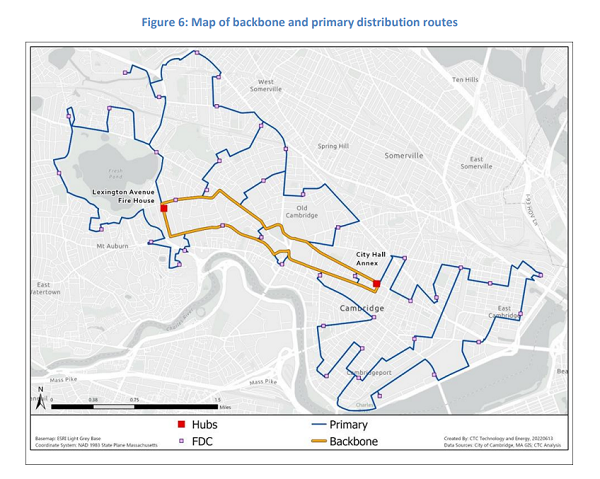

All told, the study envisions deploying 130 miles of fiber both aerially and underground that “will vary between 12- and 288-count based on the projected need in the area,” with a backbone that ranges from 144- to 288-count cables.

City councilors debate familiar questions, skepticism recedes

When CTC presented the results of the feasibility study in March, it proved to be a real eye-opener for one skeptical City Councilor.

As reported by Cambridge Day, Councilor Burhan Azeem said, “it doesn’t sound like it would be as big of a construction project as I was initially worried about.”

“I was a little bit skeptical of municipal broadband because of the cost of $200 million and all this time and energy and effort. And the benefits weren’t clear to me. This conversation has been really helpful in convincing me otherwise.”

When councilors asked about whether it was worth the investment in light of other challenges the city faced such as housing, CTC President Joanne Hovis laid out the variety of community benefits such networks provide in terms of improving economic vitality and quality-of-life – including the ability “to deliver services that we can’t imagine right now.”

It led Councilor Quinton Zondervan to observe that robust high-speed Internet infrastructure is as vital as roads, further noting: “If we went back in time 100 years, we would be debating whether to pave the roads in Cambridge. In the case of broadband, it’s creating potential new business opportunities, learning opportunities and economic opportunities for our residents.”

What’s next?

Should City Councilors decide to move forward, the study provides a “roadmap” for next steps, which includes meeting with and researching potential partners; selecting a business model; issuing an RFI; preparing and launching a procurement process; evaluating bids and selecting partner(s); conducting final negotiations; and awarding a contract.

As for CTC’s recommendation on which business model to pursue, the study says that should the city decide to move forward, CTC recommended the city pursue either building an open-access dark fiber network and lease it to multiple private providers, or enter into a public-private partnership where the private provider shoulders most of the financial risks while allowing the city to retain “long-term ownership” of the network.

Roy Russell, founding member of Upgrade Cambridge, told ILSR he was pleased with the study and the progress city leaders seem to be making to explore how they can bring more reliable and affordable competition to the market.

“One reason municipal broadband runs into trouble, in the few that have had problems, is because they either underestimated the costs or overestimated the revenue,” Russell said. “That’s why I think this study is great because it’s a conservative analysis with plenty of contingencies built in.”

Should the city be successful in building a citywide fiber network, “even for the people who wouldn’t switch (to a new provider), they still benefit greatly from competitive pressure – better service, cheaper rates. Now, there’s no way for the city to monetize that. But, it benefits everyone. So the city should see that, and not look at this as a business proposition in terms of: how are we going to make money off of this,” Russell said.

“The city should see this as infrastructure investment the same way we invest in schools, roads, and sewers. It’s about providing services. I mean, we’ve spent somewhere around $500 million renovating our schools. And the schools are great. So I see this (construction cost) as the price to get competition in the city. The phrase ‘Feasibility Study’ implies: can we do this? There isn’t any question about the technical feasibility. That’s well known. It’s entirely feasible. So the question is: what is the cost and how much value does it brings the city?”

Now that the study has been completed, Russell says his group has a simple ask – that city leaders “proceed in an open and deliberate manner to better understand the alternatives and the decisions that need to be made. We believe if they look at the value it brings, the answer will be to definitely move ahead.”

This article originally appeared on the Institute for Local Self Reliance’s Community Broadband Networks project on May 30, 2023, and is reprinted with permission.

Member discussion