Section 230 Executive Order Questioned by Federal Communications Commissioner Geoffrey Starks and Legal Experts

June 17, 2020 — “Section 230 is on fire in D.C.,” said Eric Goldman, professor at the Santa Clara University School of Law, at a Wednesday webinar hosted by the Information Technology & Innovation Foundation. Panelists on the webinar discussed President Donald Trump’s recent executive order regardin

Em McPhie

June 17, 2020 — “Section 230 is on fire in D.C.,” said Eric Goldman, professor at the Santa Clara University School of Law, at a Wednesday webinar hosted by the Information Technology & Innovation Foundation.

Panelists on the webinar discussed President Donald Trump’s recent executive order regarding the controversial statute, as well as other recent attempts to curb its reach. On Wednesday, the Department of Justice issued new recommendations for reforming the statute, and Sens. Josh Hawley, R-Mo., and Marco Rubio, R-Fla., introduced a bill that would allow users to sue internet companies for uneven or “bad faith” enforcement of their terms of service.

Each proposal attempts to curtail the liability protections that Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act provides to online platform companies hosting third party content.

“The executive order was really the kind of stuff you would expect to hear at a President Trump for Reelection campaign rally, rather than what you’d expect to see in a legally binding document that has gone through full legal vetting by a well-functioning executive branch,” Goldman said.

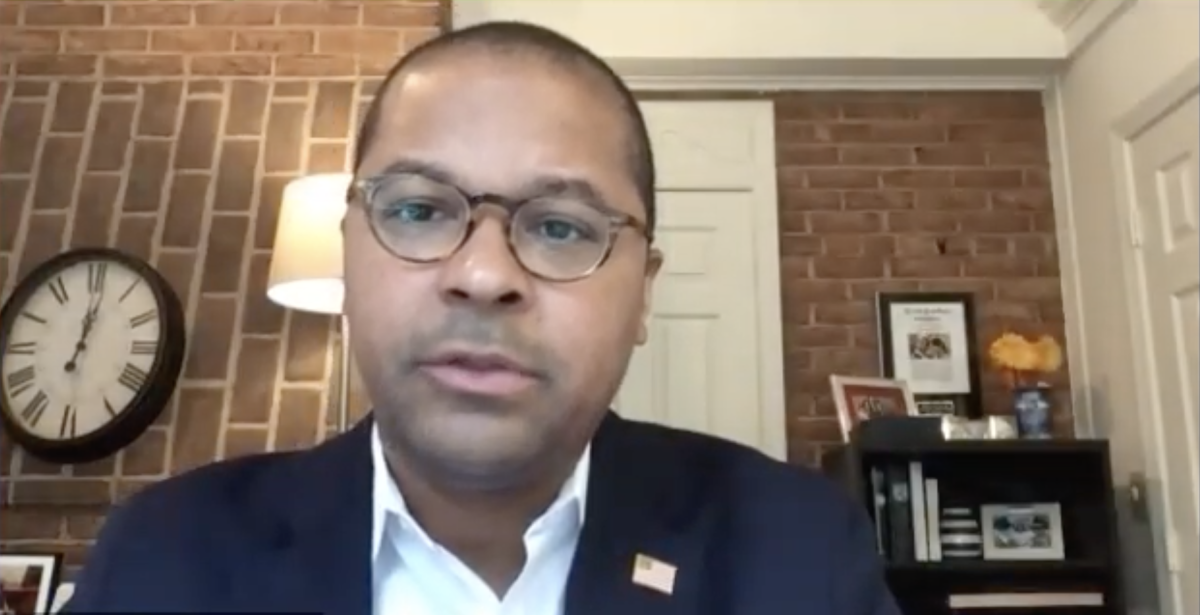

While opponents of Section 230 claim that it allows social media companies to limit free speech, Federal Communications Commissioner Geoffrey Starks pointed out that the companies themselves are protected by the First Amendment.

“In focusing on Section 230, we shouldn’t lose sight of the fact that the Constitution — not just a statute — protects private actors’ right to label, moderate, and otherwise control speech on their platforms,” he said. “The First Amendment allows social media companies to censor content freely in ways the government never could, and it prohibits the government from retaliating against them for their speech.”

The executive order directs the National Telecommunications and Information Administration of the Commerce Department to send a petition asking the FCC to propose regulations regarding Section 230.

Starks urged the NTIA to send this request as quickly as possible, rather than waiting until the prescribed deadline at the end of July.

“If, as I suspect it will, the petition fails at the threshold legal question of authority, we should say so loud and clear, close the book on this unfortunate detour and get back to the important work of closing the digital divide,” he said.

Starks also emphasized the political timing of the order.

“Whatever you think of its merits, the executive order represents the President’s clear intention to influence how social media companies operate at a time when their decisions are heavily implicated in his own electoral future,” he said.

Other experts question the need for the executive order

Kate Klonick, assistant professor at the St. John’s University School of Law, agreed, saying that “this has turned into a way to go after platforms and big tech companies because they hold a lot of power and a lot of amplifying potential for politicians.”

Goldman argued that the debate over content moderation should be framed as editorial discretion rather than censorship. Companies clearly have the right to exercise their editorial discretion in a politically biased way, he said, even if such an outcome is undesirable.

There is no evidence currently supporting the existence of political bias on social media platforms, Goldman claimed, and by definition, every single content moderation decision creates a winner and a loser.

“Those losers, over time, feel like they can look around, find other people who have the same outcome and say, ‘how come they’re all picking on us?’” Goldman said. “The losers are always going to be unhappy with the outcome they got, and they’re always going to claim that that was a result of bias against them.”

Content guidelines on social media platforms have stayed largely the same for the past several years, Klonick added. Any perceived uptick in enforcement is likely explained by the growing amount of extremist speech online.

Starks expressed skepticism about whether the FCC should even be playing a role in the regulation, explaining that the agency has power to act either when expressly directed to do so by Congress or when Congress leaves an interpretive gap to be filled.

“Neither has happened here,” he said. “Section 230 provides a self-enforcing rule for courts to apply in private litigation and does not give the FCC an enforcement or administrative role.”

“That the president might find it more expedient to influence a five-member Commission than a 538-member Congress is not a sufficient reason, much less a good one, to circumvent the constitutional function of our democratically elected representatives,” he added.

Klonick noted the importance of a commissioner arguing that his own agency is not supposed to have a certain authority.

“The phrase ‘when you’re a hammer, everything’s a nail’ comes to mind, and if you’re actually going, ‘oh no, this isn’t a nail,’ and you’re hearing it from the hammer, I think that’s pretty significant,” she said.

Member discussion