FCC’s Net Neutrality Rules Come With a Few Tweaks

A decision to forbear from applying Title II’s rate regulation provisions would preempt New York’s law, argues one scholar.

Ted Hearn

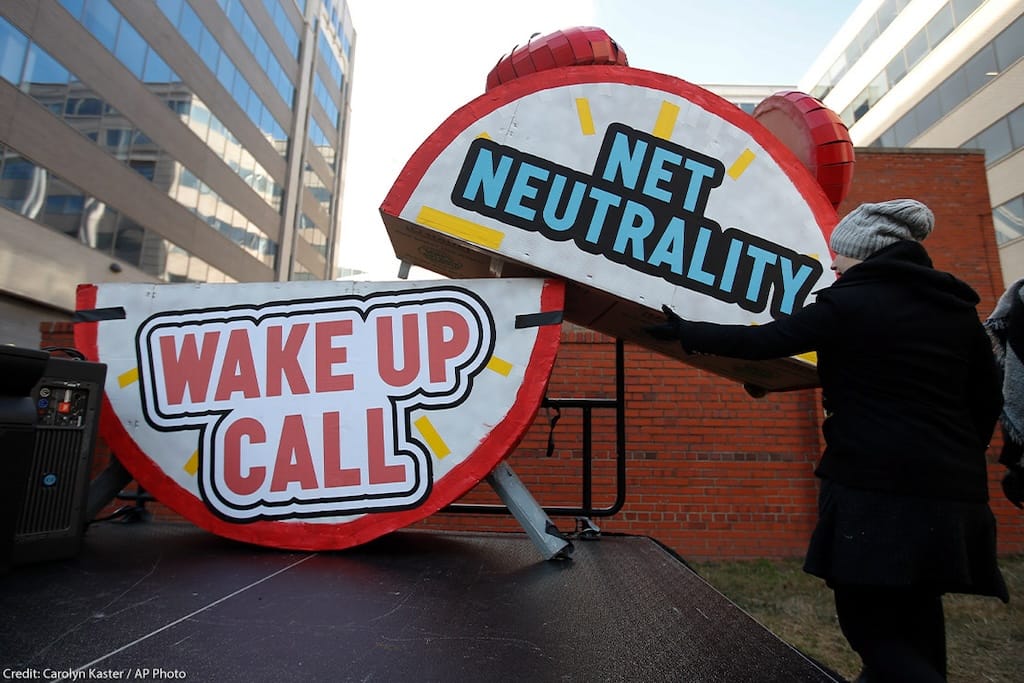

WASHINGTON, May 10, 2024 – In recent weeks, the Federal Communications Commission’s Net Neutrality rules received a slight makeover – most of it coming as a result of emphatic pressure applied by various lobbying organizations.

The final rules released May 7 were not substantially different from the draft that FCC Chairwoman Jessica Rosenworcel released to the public on April 4. The final rules include the three brightline prohibitions – no blocking, no throttling, no paid prioritization – backed by the general conduct standard and transparency rules under the common carrier framework within Title II of the Communications Act.

In the run up to the FCC’s climatic vote on April 25, Rosenworcel allowed a few tweaks here and there that reflected appeals made by interested parties in discussions that took place with FCC Commissioners, their advisors, and senior commission officials in the Wireline Competition Bureau.

Some lobbyists got their way, while others clearly did not.

A big winner was Akamai Technologies. The caching and content delivery network (CDN) provider sought assurances that its business ties to broadband Internet Service Providers would not be treated as paid prioritization, which is largely banned under the Net Neutrality rules. Akamai even proposed the language it wanted inserted into the final order. And it got what it wanted, word for word.

The FCC’s order now reads: “Consistent with the 2015 Open Internet Order and the record, we clarify that the ban on paid prioritization does not restrict the ability of a [Broadband Internet Access Service] provider to enter into an agreement with a CDN to store content locally within the BIAS provider’s network.”

Rosenworcel also felt pressure from small ISPs who sought a wholesale exemption from the Net Neutrality rules, claiming that compliance costs would reduce investment in broadband networks. WISPA, a trade association for fixed wireless access providers, asked for an exemption covering all ISPs with 250,000 subscribers of fewer – a threshold that included just about every ISP except for a handful of industry giants. But Rosenworcel did not budge.

“We acknowledge that regulation generally, and open Internet regulations in particular, can affect market participants differently. On balance, however, we conclude that our approach is unlikely to reduce, and would likely promote, overall investment and innovation in the Internet ecosystem,” the FCC said.

On Universal Service Fund issues, broadband ISPs were vulnerable at the federal and state levels. But Rosenworcel decided to shield ISPs from contributing to the federal fund for now, over the boisterous objections of INCOMPAS, CCIA and NTCA. High-profile names like Affordable Broadband Campaign spokesperson Gigi Sohn and Michael Calabrese of New America’s Open Technology Institute also scolded Rosenworcel.

In an issue that garnered little attention, cable ISPs like Comcast, Charter and Cox sought new language expressly barring states from requiring ISPs to contribute to state USF programs. The cable ISPs reminded the agency that it took that position in the 2015 Net Neutrality rules that were reversed a few years later.

According to FCC and industry sources, footnote No.1,476 in the final order reaffirmed the agency’s commitment to the 2015 policy, yielding a win for the cable ISPs.

In pertinent part, footnote 1,476 reads: “ … Pursuant to our forbearance from 254(d) to maintain the status quo for contributions based on the provision of [Broadband Internet Access Service], and consistent with the 2015 Open Internet Order, we maintain the status quo with respect to states’ ability to impose state-level contribution obligations on the provision of BIAS for state universal service programs.”

Broadband BreakfastBroadband Breakfast

Broadband BreakfastBroadband Breakfast

The cable ISPs were pleased the FCC adopted a national approach on USF funding.

“Despite intense pressure from several public interest and telecom industry groups to allow states to assess broadband subscribers with Universal Service Fund fees, the FCC determined that it should forbear from this obligation which could have raised consumer home Internet bills by billions of dollars if approved,” an industry source said.

The FCC’s decision to ban states from demanding USF contributions did not establish a pattern. In some key areas, the FCC is taking a wait-and-see approach with regard to state action.

For example, the FCC did not forbid states from adopting their own Net Neutrality laws. In examining California’s Net Neutrality law, the FCC said it “appears largely to mirror or parallel our federal rules [and] we see no reason at this time to preempt it.”

More controversial is the FCC’s approach to state laws that create affordable broadband programs and whether the laws are a form of impermissible rate regulation.

As the April 25 vote approached, FCC Commissioner Geoffrey Starks, a Democrat, had new language inserted into the order to ensure the agency did not slam the door on state affordability programs. In that regard, the FCC said it did not receive “a focused and robust record or discussion concerning any particular state broadband affordability program,” adding that it would not “address any particular program.”

To underscore its hands-off approach, the FCC said, “We also clarify that the mere existence of a state affordability program is not rate regulation.”

That was going too far in the view of Republican FCC Commissioner Brendan Carr.

In his 58-page dissent, Carr said that by classifying ISPs as common carriers under Title II and forbearing from rate regulation, the FCC had nullified New York state’s Affordable Broadband Act. Carr said the New York law was “naked rate regulation that is plainly preempted” by the Net Neutrality rules.

The day after the FCC adopted the Net Neutrality rules, a panel of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 2nd Circuit upheld New York’s ABA, saying the state was free to do so while ISPs were classified as unregulated information service providers under Title I of the Communications Act.

But the 2nd Circuit was nearly unequivocal in saying New York’s ABA was invalid when ISPs are common carriers under Title II and the FCC has used its forbearance authority to forbid rate regulation. The FCC did both in the Net Neutrality rules.

“If the FCC decides to forbear from imposing a common carrier obligation, the states are prohibited from imposing that same obligation on the telecommunications service,” Circuit Judge Alison J. Nathan said in her panel opinion.

In an essay published Friday, Boston College Law School Professor Daniel A. Lyons agreed with Carr.

“The Second Circuit recognized that a decision to forbear from applying Title II’s rate regulation provisions would preempt New York’s law,” Lyons said.

New York state’s Affordable Broadband Act requires state ISPs to offer broadband at $15 per month for 25 Mbps, or $20 per month for 200 Mbps, to qualifying consumers.

What isn’t clear for now is whether the FCC will view New York’s ABA rate controls as equivalent to another state’s embrace of the Affordable Connectivity Program (ACP) model that would provide monetary monthly discounts from state coffers.

To underscore that it sees a key role for states, the FCC inserted this footnote: “The BEAD grant program established by the IIJA, for example, requires state BEAD programs to ensure that ISPs offer a ‘low-cost broadband service option’ for eligible subscribers.”

Member discussion