Kentucky Deploys State-Wide Fiber Network Through Public Private Partnership with Macquarie Capital

LEXINGTON, Kentucky, September 21, 2015 – The lieutenant governor of Kentucky, a bevy of state officials and their private sector counterparts here celebrated the finalization of the deal to build a $324 million broadband infrastructure project. The project, KentuckyWired, is a public-private partn

LEXINGTON, Kentucky, September 21, 2015 – The lieutenant governor of Kentucky, a bevy of state officials and their private sector counterparts here celebrated the finalization of the deal to build a $324 million broadband infrastructure project.

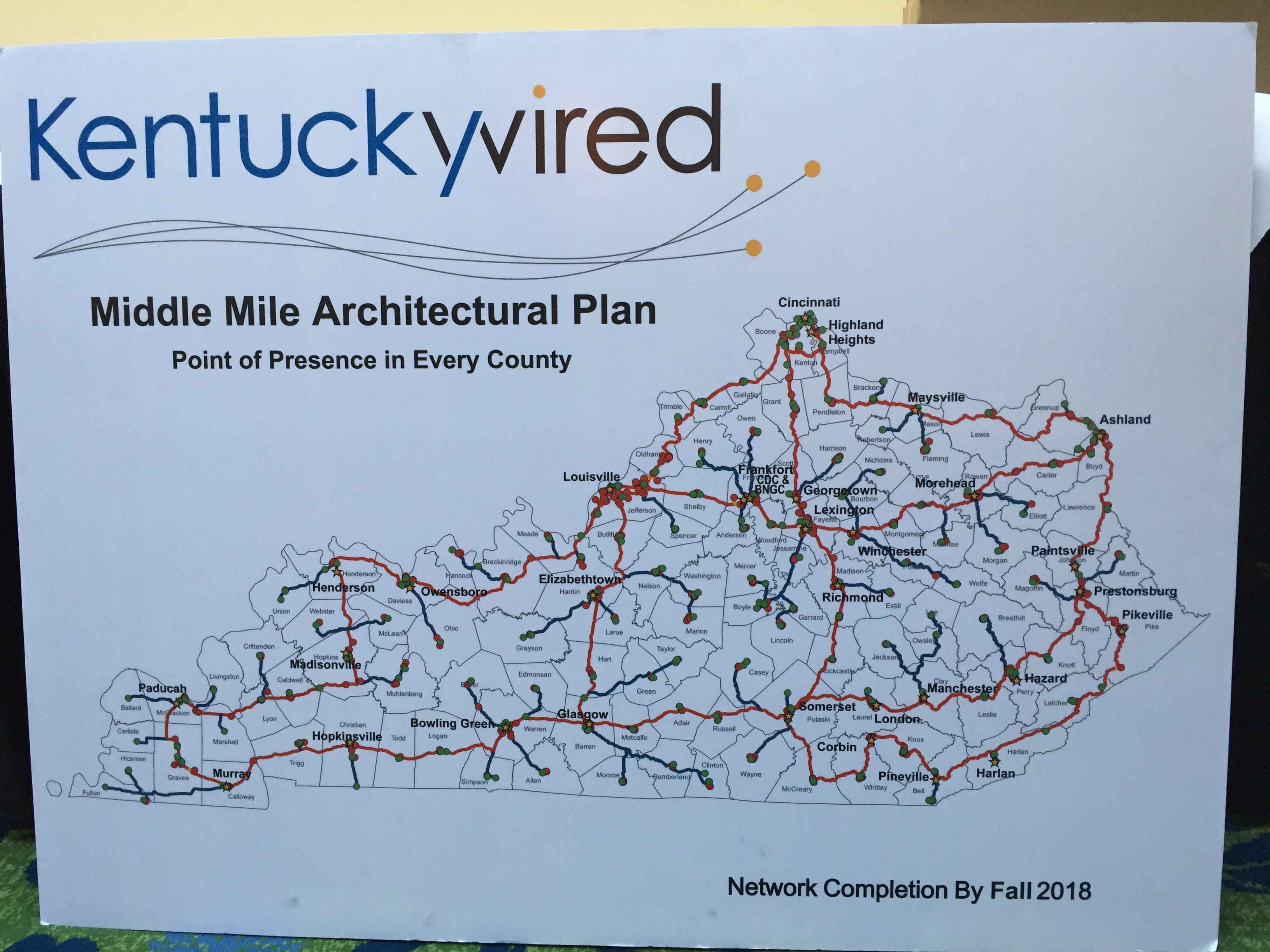

The project, KentuckyWired, is a public-private partnership (also dubbed a PPP) of the state and of the Australian financier Macquarie Capital. It is a 3,400-mile open access “middle mile” network that will span all 120 counties in the Commonwealth of Kentucky.In planning, financing and negotiating stages for nearly a year, the Macquarie project closed on September 3, 2015. Bonds are set to be issued and construction of the network – albeit in very early phases – has begun.When completed in 2018, the network will include six fiber rings around regions of the state, and fiber connections to at least one point in every county.The Kentucky Wired network was the highlight and toast of each of four days at the Broadband Communities economic development conference here.It was lauded both for its open access nature and for its unique financing structure: “The KentuckyWired transaction is the first time a PPP has been able to access the tax-exempt market, where that PPP is not eligible for exempt private activity bonds,” according to a Macquarie flyer.This unique financing structure, in which Macquarie Capital shares with the state both the benefits and the risks of the project, was touted as a model for broadband infrastructure projects throughout the country.The project will “hopefully be an example for the rest of the United States,” said Lt. Gov. Crit Luallen, speaking at a luncheon on Wednesday. Speaking of Gov. Steve Basheer, she said that “this whole broadband initiative is one of the most significant things he has done in his career, and he has had a long career.”A Private Sector Company Building a State’s Project

At the core of the project are 288-count strands of fiber-optic wires that will connect Kentucky’s counties, delivering dedicated high-speed fiber broadband to 1,100 anchor institutions. These are generally the schools, libraries, hospital and other government sites across the state.Although the network is being built by the private sector company Macquarie and a range of national and local subcontractors, the network will be owned and controlled by the state through a newly-created entity, the Kentucky Communications Network Authority.The state and the federal government provided seed funding. But the vast bulk of the $324 million network will be funded by debt and by equity raised by Macquarie.In exchange, Macquarie receives an annual concession fee of about $29 million. As the business model for the network came to be defined, this annual funding steam comes from the state moneys already spends on broadband connectivity, now redirected to Macquarie. Indeed, the exact size and scale of KentuckyWired were determined by “backing into” the annual amount already paid to other companies for lower-speed internet. Now, advocates say, Kentucky will get a better level of service for those government facilities connections — and the state will get the benefit of an open access network.The important benefits of open access networks should not be understated. Under the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act, the federal government invested almost $7.2 billion into broadband projects across the country. Most of the funds went to fiber-optic infrastructure, and most were for middle-mile investments. Such funding came with the requirement that these middle-mile networks be “open access.” That means that private companies could connect and offer last-mile broadband services within the local regions.

Indeed, the exact size and scale of KentuckyWired were determined by “backing into” the annual amount already paid to other companies for lower-speed internet. Now, advocates say, Kentucky will get a better level of service for those government facilities connections — and the state will get the benefit of an open access network.The important benefits of open access networks should not be understated. Under the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act, the federal government invested almost $7.2 billion into broadband projects across the country. Most of the funds went to fiber-optic infrastructure, and most were for middle-mile investments. Such funding came with the requirement that these middle-mile networks be “open access.” That means that private companies could connect and offer last-mile broadband services within the local regions.Recovery Act investments in open access middle-mile networks has increased broadband competition, and hence created faster speeds and better service and lower prices. Importantly, these middle-mile networks offer the ability for cities and others to build local Gigabit Networks off of middle-mile connectivity.

The Politics Behind the Beginning of KentuckyWired

Many states benefitted from extensive middle-mile projects in recent years, including California, Illinois, Maryland and North Carolina.But Kentucky didn’t have the right opportunity at the right time. Indeed, the only Recovery Act infrastructure project awarded exclusively within the state was a modest $535,308 project in Owen County.Luallen said that while Kentucky has been forward-thinking in some aspects of technology innovation, “Kentucky consistently ranked at the bottom for broadband. In the latest state of the internet report, Kentucky ranked dead last.”Likening broadband to electricity, water, sewer and other utilities, she highlighted the necessity of fiber-optic capacity for economic development, for improving health care, for enabling first responder communications, and for enhancing consumer benefits such as better cellular service.Additionally, the coal-producing prowess of the eastern, Appalachian portion of the state has been badly hampered by growing concerns about climate change, and by regulations on coal.Democratic Gov. Steve Beshear teamed up with Republican Rep. Hal Rodgers, who represents the region in Congress, about collaborating across party lines to benefit Eastern Kentucky. In the fall of 2013, they created SOAR, Shaping Our Appalachian Region, to find solutions.

“This push for higher broadband was something that emerged from SOAR,” said Luallen. Looking beyond partisanship, the initiative began to focus on broadband as the way to promote investment in a region battered by “dramatic changes in the coal industry.”

In spite of the region’s poverty and remoteness, “broadband can level the playing field despite physical or geographic isolation,” she said. By contrast, “spotty or overpriced broadband stifles entrepreneurship.”With support from Rodgers, chairman of the House Appropriations Committee, the state received $23.5 million in federal funds, and the Kentucky General Assembly allocated $30 million in state funds last year. It also has support from the Appalachian Regional Commission.“The remaining funding will come from the private sector, and the starting point for financing is that we began with existing payments that the state is making for information services [connectivity] to universities, public schools and state agencies,” she said. Those funds are between $26 million and $29 million a year.“Since the state already pays for them, those funds will be transitioned to pay for the network,” providing “a stable foundation” for the middle-mile network, said Luallen. Additionally, as the owner of the network, the state “will benefit from the financial gains one this is fully operation and it begins to turn a profit.”Macquarie’s Central Role in Building Kentucky’s State Network

Speaking on a variety of sessions throughout the conference, Nick Hann, senior managing director of Macquarie, described the network as providing a “transformative power for the Commonwealth of Kentucky.”Because of the network’s wide footprint across the state, and because of its open access nature, it will enable multiple “last mile” Gigabit Networks to be built throughout the state.Those are likely to happen next in the state’s major cities of Louisville and Lexington. Speaking at Thursday’s luncheon panel, Lexington mayor Jim Gray asked audience members involving in building Gigabit Networks to raise their hands. Many of them did.“You all represent the nation’s fiber army,” he said. As a result of their efforts, he said, “Kentucky is at the forefront in the nation with their open access and open infrastructure model.”Added Aldona Valicenti, chief information officer for the City of Lexington: Fiber optics “is not just about warehouses anymore. It’s about just-in-time everything.”“We need to invest today so that we can thrive today and in the future,” said Valicenti, who praised the role that Next Century Cities has played in facilitating the city’s and the state’s plans for fiber-optic networks.In a panel with the public and private officials most directly responsible for the Macquarie partnership, Lori Flanery, secretary of the Kentucky Finance and Administration Cabinet, said that Kentucky was able to avoid the mistakes of other states by visiting and learning from their experiences.

“Twenty years ago, things would have been differently,” she said, referring to the newly-available opportunity to build with companies in public-private partnerships.

“Most states haven’t gotten to the point that they know what their [annual broadband] spend is,” added Steve Rucker, deputy secretary of Kentucky’s technology department. Knowing that the state was already spending at least $26 million annually gave it the ability to plan a network with a payment in that amount.

Hann said that every state in the nation could do something similar: Reallocate what it spends on inferior-quality broadband, and use that to fund a state-wide Gigabit Network.

Although the discussion at the conference was largely on the network’s middle-mile component, Macquarie and its partners also highlighted future last-mile benefits.“When we first came in and did our analysis, we found a huge amount of last-mile fiber within the state,” said Mike Lee, chief operating officer of Macquarie partner First Solutions.

Unfortunately, the last-mile was scattered and unconnected to a bandwidth-intensive information highway, he said. “They had built themselves a beautiful island. The problem lay not in the last mile, but in the middle mile,” which lacked robust access.

Generally, the problem for broadband deployment elsewhere in the country is the reverse: There is middle-mile competition, but not sufficient last-mile investment.

Hann described fiber-building as a natural extension upon Macquarie’s background as the constructor of roads, bridges, airports and pipelines. “We are building the highway, not regulating which cars or trucks drive on it — all of that will still be determined by the market,” he said on the panel.“Fiber is such a good fit with the PPP model because fiber is not complicated, not cutting edge,” Hann said, distinguishing the infrastructure from the applications and content that ride on top of fiber wires. “It is a basic utility, a 30-year-plus life asset, and like the electric cable of the last century, or the water line, or the road.”Drew Clark is the Chairman of the Broadband Breakfast Club. He tracks the development of Gigabit Networks, broadband usage, the universal service fund and wireless policy @BroadbandCensus. He is also Of Counsel with the firm of Best Best & Krieger LLP, with offices in California and Washington, DC. He works with cities, special districts and private companies on planning, financing and coordinating efforts of the many partners necessary to construct broadband infrastructure and deploy “Smart City” applications. You can find him on LinkedIN, Google+ and Twitter. The articles and posts on BroadbandBreakfast.com and affiliated social media are not legal advice or legal services, do not constitute the creation of an attorney-client privilege, and represent the views of their respective authors.

Member discussion