Mobile Technology Aided the Growth of Black Lives Matter, But Will Hashtag Outrage Lead to Change?

September 21, 2020 — In the United States, widespread public use of mobile phone cameras and social media has thrust the longstanding issue of police brutality against Black Americans into the national spotlight like never before. Delving deeply into the subject of how digital tools have contributed

Jericho Casper

September 21, 2020 — In the United States, widespread public use of mobile phone cameras and social media has thrust the longstanding issue of police brutality against Black Americans into the national spotlight like never before.

Delving deeply into the subject of how digital tools have contributed to the goals of anti-brutality activists, panelists at a Brookings Institution event on September 14 detailed the rise of the Black Lives Matter movement and whether the explosive growth of the hashtag #BLM might result in any institutional change.

In the summer of 2014, videos, images, and text narratives of violent encounters between police officers and unarmed Black people circulated widely through news and social media, spurring public outrage.

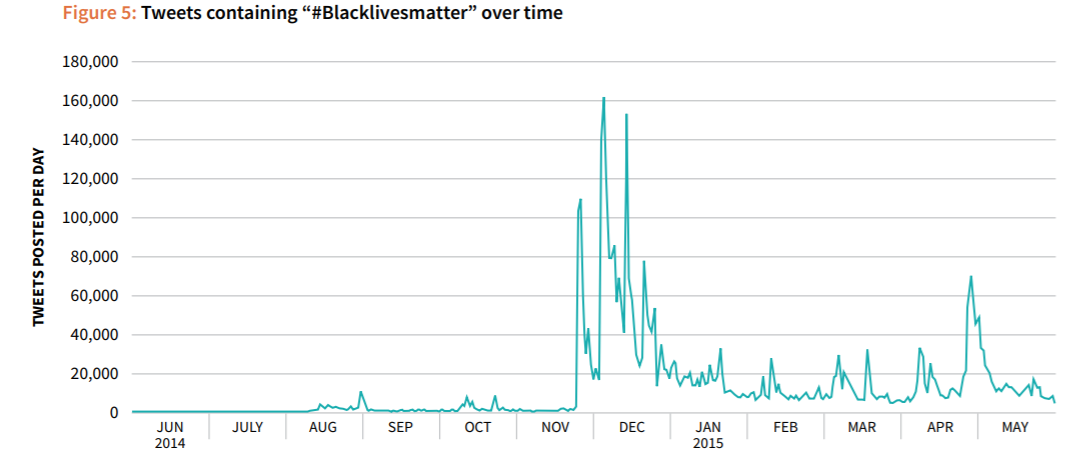

“A large digital archive of Tweets started in 2014, when Michael Brown was killed,” said Rashawn Ray, professor of sociology and executive director of the Lab for Applied Social Science Research at the University of Maryland.

Media activism fueled by the deaths of Michael Brown and Eric Garner gave rise to Black Lives Matter, or #BLM, a loosely-coordinated, nationwide movement dedicated to ending police brutality, which uses online media extensively.

The panelists referenced the “Beyond the Hashtag” report authored by Meredith Clark, assistant professor at the University of Virginia, analyzes the movement’s rise on Twitter.

“Mobile technology became an agent of change,” said Mignon Clyburn, former commissioner at the Federal Communications Commission, referring to the 2007 introduction of the iPhone as a turning point in the way individuals utilize devices. “Devices became smaller, less expensive, and more ubiquitous,” said Clyburn, “we are now seeing a global, mobile revolution.”

Increased accessibility to mobile devices and social media cracked open doors previously kept tightly shut by pro-corporate, pro-government gatekeepers of the media, which spread anti-Black ideologies. Mobile devices initiated a leveling of the media playing field, allowing for marginalized groups to intervene in dialogues.

“Black Americans have the opportunity to share distinctively what is happening to us,” said Nicol Turner Lee, senior fellow in governance studies and the director of the Center for Technology Innovation at the Brookings Institute.

“These videos show our humanity, and how it is destroyed and undermined,” added Kristen Clarke, president and executive director of the National Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under Law.

While videos taken to report instances of police brutality are critical resources, they come with significant consequences for those filming and viewing them.

In order to record an instance of police, an individual has to be courageous, as many citizen journalists attempting to capture an act of police brutality, end up a subject of cruelty.

“You have the right to record protected under First Amendment,” Clarke informed, urging that officers be trained on respecting citizens First Amendment rights to film.

While recording instances of police brutality is distressing in itself, sharing the video online, although necessary, amplifies the video’s power to traumatize indefinitely. “There will no doubt be a generation of children that will be traumatized,” by repeatedly seeing images of Black Americans brutalized by the police, said Lee.

Clarke urged individuals who decide to share content, to do so with a trigger warning.

While digital tools have enabled video evidence of brutality to be caught, amass widespread attention, and cause public outrage, as of yet, it has not translated into real-life justice for Black individuals. Difficulty to bring prosecution against excessively violent officers remains.

Clarke noted that police union contracts are barriers to reform. “The terms of collective bargaining agreements allow officers to see video evidence before reporting on how the events transpired,” detailed Clarke.

Ray called for the passage of the George Floyd Justice in Policing Act, H.R. 7120, introduced by Rep. Karen Bass, D-California, which he said was currently ‘collecting dust’ in the Senate.

The bill would establish new requirements for law enforcement officers and agencies, necessitating them to report data on use-of-force incidents, obtain training on implicit bias and racial profiling, and wear body cameras.

Member discussion