Southern Ute Indian Tribe Transforms Reservation With Open Access Fiber Network

When service was lit up in May, the network became the only open access network owned by a tribal government.

Jessica Auer

Among the burgeoning number of Tribal networks being built across Indian Country, a new fiber-to-the-home (FTTH) network spanning the Southern Ute Indian Reservation is unique.

When service was lit up in Ignacio, Colorado in May, the network became the only open access network owned by a Tribal government, providing its residents with a choice between two different Internet Service Providers offering lightning-fast connection speeds.

Five years in the making, the Southern Ute network is not only the first Tribally-owned open access network, it is also among the first of the new fiber projects funded by the Tribal Broadband Connectivity Program (TBCP) to start offering services.

With a strong commitment from Tribal leadership, savvy decision-making, and strategic vision, the Tribe has been able to fundamentally reshape the broadband market in its region, increasing speeds and competition while lowering prices.

Slow speeds and high prices fuel mission to 'bust that monopoly'

As with many other Tribally-owned networks, the Southern Ute Indian Tribe’s broadband journey began with a recognition that the existing telecommunications infrastructure on the Reservation simply could not meet the needs of the modern moment.

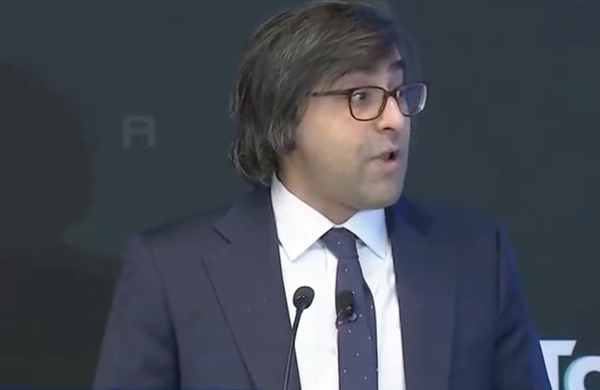

Tribal Council Chairman Melvin J. Baker tells ILSR that many in Tribal leadership “realized we’ve needed it for quite some time.”

Southern Ute Shared Services Chief information Officer Jeff Engman agreed, noting that the Tribe began working on broadband as early as 2019.

Still, the pandemic added a sense of urgency to those efforts, like it did in many other communities.

The gap between the kind of Internet access that residents had and what they needed, Chairman Baker said, became “really apparent” as schools and other vital services moved online. Even Tribal leadership felt the pinch.

Chairman Baker and Engman shared with ILSR two primary connectivity challenges on the Reservation: speed and price.

In 2020, the Tribe undertook a community-sourced speed mapping project and found startling results. More than 75 percent of Tribal residents surveyed were getting speeds of less than 7 Megabits per second (Mbps) upload and 2 Mbbs download, far below the FCC’s definition of minimum broadband speeds.

Most residents had access to only DSL or unlicensed fixed wireless as options. In some areas, there was not even a mobile option, creating coverage gaps that caused special challenges for first responders.

“The other problem,” Engman says, “was the cost,” noting that he currently pays twice what he will pay on the new network for a tenth of the speed.

Lurking behind both of these problems was another familiar culprit: monopoly providers charging “exorbitant rates” for second-rate service. A monopoly on backhaul also drove up end-user prices.

“They made it so wireless providers couldn’t even really tie in without paying a high cost,” Engman says. “So we wanted to bust that monopoly.”

Finding the righ fit with open access model

Ultimately, in order to “bust that monopoly” and improve speed, choices, and prices, the Southern Ute Indian Tribe decided to blanket the Reservation with open access fiber.

Though the Tribe initially considered relying exclusively on the 2.5 GHz license it obtained in the Rural Tribal Priority Window to build a last-mile wireless network, new funding opportunities encouraged it to think bigger. Or, as Chairman Baker put it:

“If we’re going to do it, let’s go big. You know, let’s do it right for the long term.”

With the support of a $44 million grant from the Tribal Broadband Connectivity Program and more than $10 million in funding from state programs, the Tribe launched its plan to bring fiber service to 6,700 homes on the Reservation, which is about 75 miles long and 15 miles wide. Interconnection points in the area are sparse.

To reach every household on the Reservation with high-speed Internet – and erect cell towers to enhance mobile connectivity for emergency responders – would require a massive undertaking to deploy 500 miles of fiber.

The challenge was made all the more difficult because of the “complicated and lengthy permitting” processes, an all-too-familiar obstacle for Tribal broadband projects. The Southern Ute Indian Tribe’s project involved crossing Tribal trust land, fee land, and non-Tribal land, and liaising with the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA), Forest Service, Bureau of Reclamation, and the Colorado Department of Transportation.

In April, the Tribe celebrated a major milestone when the first subscribers were lit up for service in Ignacio, the largest community on the Reservation. Nearly 900 households can now sign up for high-speed service for the first time ever.

Still in the first phase of a multi-step process, Chairman Baker noted the Tribe expects to complete grant-funded expansions to the backbone over the next two years that will “provide much-needed resiliency to our network” as well as extend service to homes in the western part of the Reservation.

The scale of the project is part of the reason the Tribe opted to build an open access network.

“There was a lot of debate and discussion” over the model, Engman said. But, after researching municipally-owned open access networks, the Tribe decided the open-access model would be the best fit.

Tribal leaders decided to contract with an outside partner, Bonfire Infrastructure, to operate the network – an arrangement Engman said would allow the Tribe to execute its plan without “signing up for all the things that it took to operate and sell that network.”

Moreover, rather than being an ISP itself, Engman said, “we want the competition. We want to help local Internet service providers succeed.”

Public-private partnerships remain rare among Tribally-owned broadband projects, and the choice of partner is key. For a project of this importance, the Southern Ute Indian Tribe was looking, first and foremost, for a company that demonstrated “respect for the Tribe’s position of leadership in the community.”

Ultimately, what mattered most to the Tribe was its ability to own the infrastructure. “We wanted to put the Tribe in the driver’s seat,” Engman said, adding that owning the network infrastructure will allow the Tribe to think strategically about the future, adapt as needed, and ensure residents remain connected for years to come.

Commitment and trust across tribal government

Engman credits the commitment of Tribal leadership for the comprehensive vision and the quick pace of the broadband project. Chairman Baker and Tribal Council, Engman said, have remained engaged and supportive throughout the arduous project, eager to hear updates of the progress and hands-on in decision making.

Tribal Council also demonstrated their confidence in the project by committing actual resources to it when its success was not assured.

The Tribe spent money on design and engineering in an effort to have a “shovel-ready” that was competitive for funding. But, the financial commitment of Tribal Council went even further - they authorized the pre-purchase of fiber, conduit, and other materials before any grants came through.

“It was a risk for the Tribal Council to approve,” Engman recalled. “But if we waited, the price of fiber, conduit, and electrical components were probably going to go up anywhere from 30 to 40 percent.”

That fateful decision not only kept costs down on the project, it also allowed the Tribe to continue making steady progress.

For his part, Chairman Baker credits the “foresight” and quality work of the Tribe’s cross-departmental broadband team. Though it was up to Council to approve the purchases, it was Engman and his team, Chairman Baker noted, that foresaw the changes in the market and came to Tribal Council with the proposal.

Getting and keeping people online in the long term

The Tribe’s broadband project has been embraced by the residents – many of whom had grown weary of slow speeds and high prices.

“Response from the community I get is very positive,” Engman said, adding that subscribers have been “absolutely amazed” to be getting “big city speeds in rural, small town Colorado.”

One aspect of the new service that’s generating excitement is the lower cost. After careful and repeated business modeling and planning, Tribal planners were able to settle on a price point that supported both subscriber affordability and long-term network sustainability.

Subscribers can now pay between $70 and $80 dollars for symmetrical speeds of 250 Mbps, about half the cost of the existing (slower and less-reliable) services. And even with more reasonable rates, Engman said the network is expected to earn enough revenue to “provide the ongoing operations and maintenance money needed to maintain and possibly grow the network” without ongoing Tribal funding.

Beyond building the infrastructure, the Tribe is also committed to expanding its digital inclusion efforts, which has important repercussions for both community impact and, in the long run, network sustainability. With the support of grant funding, the Tribe has been able to launch device distribution programs and offer digital navigation services and digital skills training.

Those efforts, Chairman Baker said, are key to maximizing the network’s value. “The team is willing to work with everyone, whoever has a question, especially our elders, because sometimes it’s a new thing (to them),” he said.

By lowering the barriers to getting online and increasing the confidence of new digital users, digital inclusion work can be invaluable in sustaining a small, community-owned network that must rely on broad community support.

Over the last few years, federal and state agencies have made a historic investment in Tribal broadband. For the first time, Tribal consent and set-aside policies have made it easier for many Tribes to meaningfully direct that money to self-determined broadband solutions.

The Southern Ute Indian Tribe’s new network demonstrates how Tribes can leverage these resources to transform the digital landscape across Indian County, bringing high-speed, reliable, and community-driven broadband to their communities for the first time.

The article was originally published on the website of the Institute for Local Self Reliance's Community Broadband Networks Initiative on Oct. 22, 2024, and is republished with permission.

Member discussion