Next Level Networks’ Pilot Community Fiber in Los Altos Hills Experiences Growing Service Demands

August 30, 2020 — In a neighborhood outside of Silicon Valley, amongst what native Scott Vanderlip described as “a community full of tech geeks,” residents struggled to access reliable, affordable internet, despite being able to see the headquarter buildings of some of the largest tech companies fro

Jericho Casper

August 30, 2020 — In a neighborhood outside of Silicon Valley, amongst what native Scott Vanderlip described as “a community full of tech geeks,” residents struggled to access reliable, affordable internet, despite being able to see the headquarter buildings of some of the largest tech companies from their homes.

According to Vanderlip, chair of Los Altos Hills Community Fiber, incumbent internet providers stopped extending infrastructure to the area around 15 years ago.

“AT&T U-Verse was doing well extending fiber in the area,” Vanderlip recalled during an interview with Broadband Breakfast, “before they suddenly stopped building and began charging outrageous prices to extend service.”

As a result, Los Altos Hills, California, was riddled with pockets of extreme desperation for internet access, forcing some residents to turn to satellite providers for service.

Frustrated with the lack of alternatives available to the town, Vanderlip and other residents banded together to form Los Altos Hills Community Fiber, a network of homeowners that literally owns its own fiber-optic broadband.

The company providing the know-how and coordination for this experiment in high-capacity broadband is Next Level Networks, a Sunnyvale-based company with a visionary approach to changing fiber-optic build-outs.

Next Level Networks sees Los Altos Hills Community Fiber as a test case for its unique open access financing model of ultra-high speed, community-owned internet infrastructure.

And it is there, an area overlooking but apart from Silicon Valley, that the co-venturers are attempting to fill the gaps in broadband left by monopoly-style providers like AT&T and Comcast.

Next Level Networks’ open access model

Next Level Networks’ CEO Darrell Gentry is the brain behind the open access model utilized by Community Fiber.

Unlike a corporation where one company owns the infrastructure, operates the network, and offers internet services, open access models split this conventionally vertically-integrated service model apart.

“We adapted the co-operative approach to fiber broadband,” Gentry told Broadband Breakfast.

The Community Fiber network is owned and financed by LAHCF, an entity representing its subscribers or end users, and managed by a professional operator, Next Level Networks.

Next Level Networks was selected by LACHF to head the design, configuration, installation and maintenance of its community-owned and operated fiber optic network.

“The community owns the last mile infrastructure, members own drops to their homes, and the company provides the “middle mile” fiber backhaul,” detailed Gentry.

“We leave it to the communities to build,” he said, specifying that they expect communities to take the lead on acquiring customers, which leads to an ownership mentality.

By utilizing an open access model, LACHF has secured more control over their community’s connectivity future. And for Next Level Networks, the model ensures that projects are cash flow positive on day one.

The “barn-raising” installation of Los Altos Hills Community Fiber

A unique crowdsourcing methodology aims to drive further growth

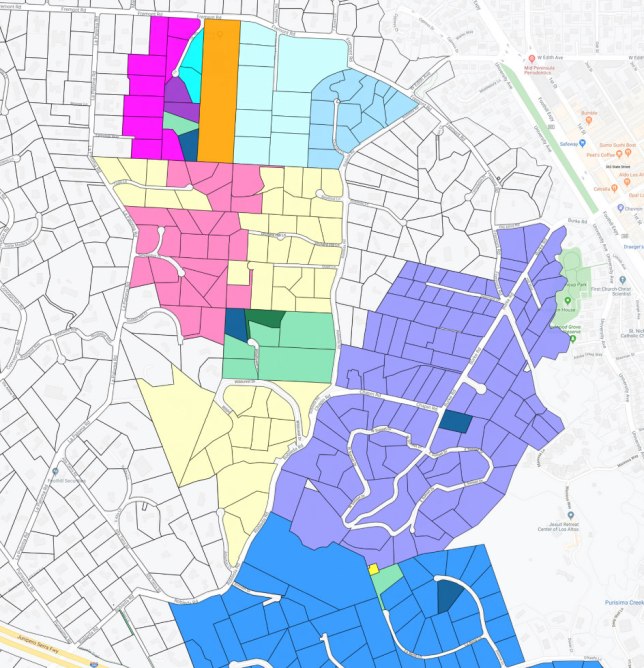

Gentry created crowdsourcing technology to gauge interest in services in order to better understand where his service model would be feasibly implemented.

Utilizing this technology, residents are able to help drive local participation by plugging in their address in Next Level Network’s crowdsourcing web site. This then can encourage their neighbors to join.

The more users that local internet champions can get to subscribe to LAHCF, the less monthly service costs.

“We divide the cost by the users and that’s how much we charge,” Vanderlip explained. “The more users, the less expensive.”

Subscribers must pay a one-time fee for infrastructure installation, which typically ranges from $3,000 to $10,000, to connect neighborhoods to the network and extend fiber from the backbone to the home.

As the costs of many internet providers continue to climb, the cost of LAHCF will instead fall as interest grows and participation increases.

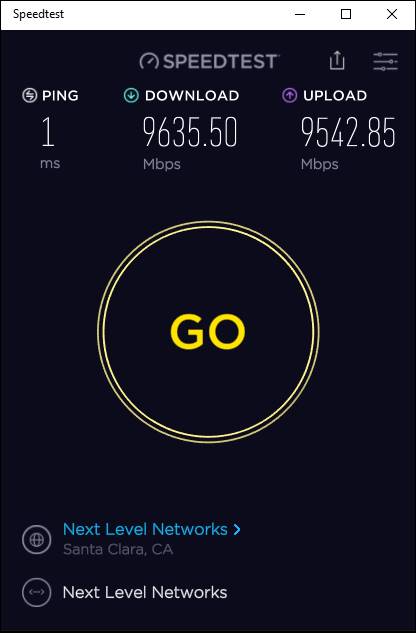

The LAH Community Fiber network currently offers 1 Gigabit per second (Gbps) upload and download speeds, but it’s built to offer 10 Gpbs, which will become available as the cost of the requisite equipment decreases, according to Vanderlip.

10 Gigabits per second symmetrical connections!

Los Altos Hill’s netizens won’t have to wait for an operator to decide they have the budget to provide more bandwidth for LAHCF subscribers: The community will decide together.

Demand has increased since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic

Service to the network went live in April of 2019, and just over a year in, community demand for the internet service is skyrocketing.

Vanderlip said that community interest in LAHCF has been exponential since the town’s working and schooling operations were shifted to the home by the coronavirus pandemic

Over 12 neighborhood projects have recently been launched by neighborhood champions all over Los Altos Hills.

As residents’ bandwidth demands have increased throughout the town, infrastructure put in place by incumbent providers has simply not been unable to keep up.

The increase of video teleconferencing, for example, has meant that “people’s internet has just stopped working,” Vanderlip said.

The Los Altos Hill Community Fiber solution offers manna for residents grappling with sluggish connections.

In an effort to gauge interest in the service, Community Fiber recently launched a survey to better understand local residents’ internet gripes.

Of the 46 responses received, 96 percent said that internet is either super or very important to them.

When asked whether they would be interested in joining the community fiber network, 75 percent indicated they were, while 27.5 percent expressed willingness to become “champions” to inform their neighbors of the possibility.

In an effort to quickly deploy service to neighborhoods with increasing interest, LAHCF is in the process of planning to deploy multi-Gbps radio links which can beam internet service in order to shorten the time of deployment to those in need while neighborhood interest continues to build.

A map of Los Altos Hills Community Fiber project areas

Incumbent providers have key weaknesses

Even though the federal government has put billions into bringing broadband to rural communities, there is still no broadband in many areas, Vanderlip said.

As an example that spurred his outrage at incumbent providers, Vanderlip personally asked a colleague working for the California Public Utilities Commission to look up different California addresses, including extremely rural addresses that he knew had limited service options, to see if federal monies were available.

If no money was available, it meant the monies had been spent with no viable options delivered.

For example, in Bumblebee, California, in the Stanislaus National Forest, Vanderlip sought information about a grant from the Connect America Fund Phase II Auction. But the area was ineligible as AT&T was awarded the money in a nearby city.

“They took the money four years ago and have not done anything with it,” said Vanderlip, saying the town still has zero broadband options, with some still using dial up internet. “They took $15 million and it’s just not there,” he complained. “It’s amazing what these companies are getting away with.”

Scott Vanderlip talking about Los Altos Hills Community Fiber over videoconference

Back in Los Altos Hills, the main incumbent is cable provider Comcast, which he said provides slows speeds during peak usage with wildly outdated technology.

“We should not be wasting any more money in metal-based technology-to-the-home,” Vanderlip said, criticizing incumbents who continue to install outdated coaxial cables.

Vanderlip personally got inspired about community-owned fiber after Comcast quoted him $17,000 to extend its service the distance of three telephone poles to his house.

“I thought that was outrageous,” Vanderlip said. “Comcast can charge whatever they want for these installs,” even though they are supposed to maintain a standard rate.

“This isn’t even that expensive,” said Vanderlip. The government “could bring fiber to the country for a small fraction of what they’re spending on other projects.”

Can the community fiber model work more broadly?

The case of Los Altos Hills Community Fiber may prove that, in the words of Gentry, “a community with a sufficient amount of interest can take its destiny into their own hands.”

“If I have the option to invest in my own community, I want to invest,” added Vanderlip, saying that the investment needed to bring about widespread economic prosperity in America is to bring fiber internet to everyone in the country. Next Level Networks’ open access model facilitates community champions doing just that.

Vanderlip directly acknowledged that “Los Altos Hills has the benefit of being a very affluent community.” And this leads to a critical question: Can the model be replicated in a less affluent areas?

Many communities do not have the financial mobility to get such a capital-intensive project, like this, off the ground, he said. But that is where Next Level Networks’ financing model may come into the picture.

Someone has to play the catalyst role within the community, as Vanderlip has done in Los Altos Hills. But with many eager to invest in their communities now, Next Level Networks aims to generate many more success stories in the future.

Member discussion