‘On the Internet, No One Knows You’re a Child’: The Short Life of Aaron Swartz, at Sundance

On the internet, no one knows you’re a child.

PARK CITY, Utah, January 23, 2014 – On the internet, no one knows you’re a child.

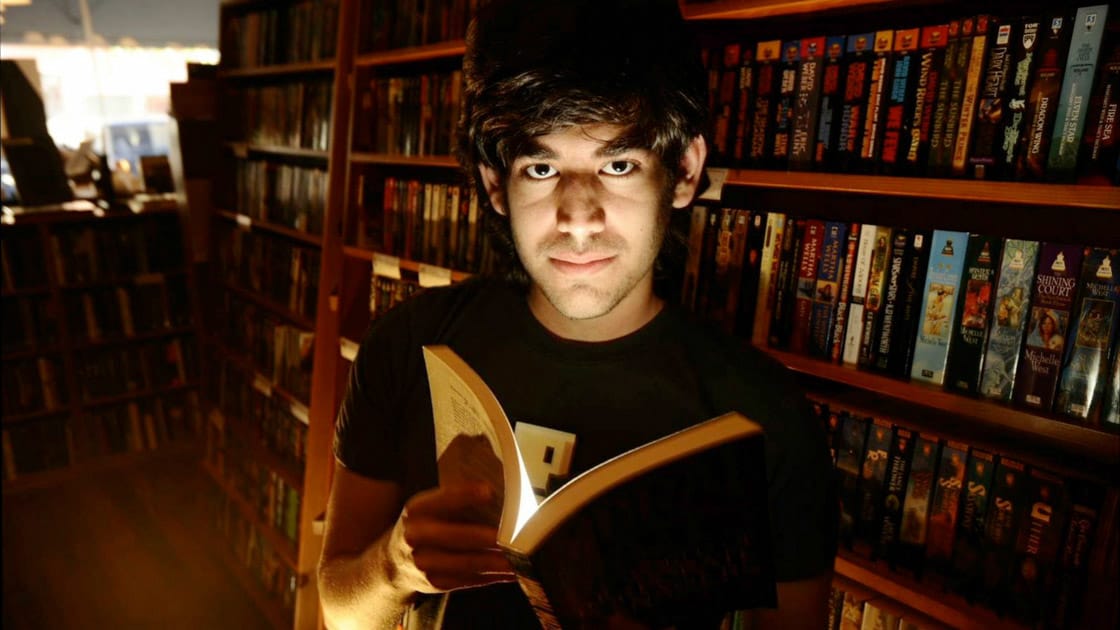

That, at least, was the message I took from watching the film about the life of Aaron Swartz. The film, “The Internet’s Own Boy,” premiered this week here at the Sundance Film Festival, during which it received a sustained standing ovation.

The documentary is a biography of, and tribute to, the all-too-short life of Swartz, who died a year ago this month, at age 26.

Swartz had been under intense pressure from the federal prosecutors in Massachusetts. Criminal charges filed against him, if proven, could have imprisoned him for 35 years. Those charges stemmed from Swartz’s having downloaded millions of articles from JSTOR, a digital library of academic journals, onto a computer at the campus of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. While it is unclear what Swartz intended to do with the articles, it seems implausible that he would have republished them in an act of copyright infringement.

On January 11, 2013, he committed suicide at his home in Brooklyn.

The film, and the life of Swartz himself, has been called several things.

On one view, it’s a parable of prosecutorial abuse, or the vast overreach of the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act, the 1986 law — passed, ironically, in the year Swartz was born — which was responsible for 11 of the 13 charges leveled against Swartz. Since his death, Rep. Zoe Lofgren, D-Calif., and Rep. James Sensenbrenner, R-Wis., introduced “Aaron’s Law” to curb CFAA’s extremes.

It’s also a tale of the blessing and the curse of the internet. Swartz said this himself, in one of the many archival clips of him included in the movie: Technologies have enabled freedom, even as they have unleased surveillance conducted by the likes of the National Security Agency.

I prefer to see the message more personally. No matter how advanced our society is, or our technologies become, the only way for a boy to grow to be a man is through the nourishment of the warm cocoon of a family. We are raised in families, and it is from them that we learn the life lessons to sustain us against a cold and often threatening world.

The director of “The Internet’s Own Boy: The Story of Aaron Swartz,” Brian Knappenberger, impressively gathered interviews from countless associates, friends, family members, and critics. These included internet luminaries as World Wide Web founder Tim Berners-Lee, Electronic Frontier Foundation attorney Cindy Cohn and technologist Peter Eckersley, author Cory Doctorow, law professor Orin Kerr, Harvard cyberlaw expert Lawrence Lessig, Rep. Lofgren, resource.org President Carl Malamud, internet freedom program officer Stephen Shultze, activist Matt Stoller, and Oregon Democrat Sen. Ron Wyden.

These are people familiar to many in the world of broadband and internet experts.

So for me, the best part of the movie was to be able to watch the interviews with his mother, his father, and his two younger brothers, as well as to see home video clips of Aaron and his younger brothers. In the film, we see not a family of crises or of extremes, but a loving father and mother who nourished Aaron’s brilliance and love of computer programming. For him, software was a tool that could magically unlock the knowledge of our universe.

The film opens and ends with clips of videotapes of Aaron as a three-year-old boy, reading a story, engaging with the camera, demonstrating his love of learning and his zeal to make a difference. As a child, he built tools to teach, and to help people to learn.

Clearly precocious, in 1999 at the age of 13, Swartz got excited about RSS, the standard for “real simple syndication” and the backbone for news readers, and social media services that would come.

He was very much a part of the culture of the internet. That culture did not and does not demand permission to innovate. Through e-mail communications, Swartz dived into the work of a standards group within the World Wide Web Consortium. Always opinionated, people started to want to meet him at technical conferences, Doctorow and Eckersley said in the film.

But while he may have had permission to innovate, he didn’t have permission to travel. For that, Aaron needed to ask his mother.

At age 13, when Swartz won second prize at ArsDigita, a competition for you people to create “useful, educational and collaborative” noncommercial web sites, he did travel from his home in Chicago to Boston. By the age of 14 and 15, he had gotten involved helping Larry Lessig to design computer-readable license for the Creative Commons alternative to copyright.

Many readers of BroadbandBreakfast.com may know Swartz. I met him around this time when, as a 15-year-old boy, he attended the oral arguments for the Eldred v. Ashcroft case before the Supreme. I had been covering Lessig’s important case challenging the longevity of copyrights from the time the case was filed. It challenged Congress’ authority to extend copyright terms from 50 years after the life of the author, to 70 years after the life of the author. That 1998 law extended corporate copyrights from 75 years to 95 years, and strategically kept the character Walt Disney from falling into the public domain. Lessig, in turn, offered Swartz one of his tickets to the oral argument.

In the film, it was his mother who noted the incongruity of Swartz’s early engagement with this adult world. Here he was, a young teenager invited to discourse on RSS or machine-readable licenses, or to follow challenges to copyright law, at an important technical conference or legal events.

“These adults regarded him as an adult,” said his mother, Susan Swartz. But she said he was just a boy.

Since Swartz’s passing, we have become uncomfortably familiar with the rest his biography: he attended Stanford University, dropping out to work on the startup and hit web site Reddit. Purchased by Conde Nast, the owners of Wired, Swartz took the money from his buyout and left to become involved projects including watchdog.net, openlibrary.org, and demandprogress.org.

Swartz also got involved in projects to help open up public domain files buried within pacer.gov, the clunky Public Access to Court Electronic Records. And, most ominously, he downloaded the articles from the academic database JSTOR at MIT, which resulted in the government’s indictment.

But at this time of remembrance, it is entirely fitting for the film to crescendo to the last, and perhaps most successful venture of Aaron Swartz’s short life: spearheading the grassroots lobbying campaign to kill Hollywood’s wish list, the Stop Online Piracy Act. Over the course of one day – January 18, 2012 – leading internet web sites like Wikipedia went dark in protest to SOPA. The act, critics said, would have crippled the internet’s domain name system. The anti-SOPA campaign turned around enough senators and members of Congress that no one on Capitol Hill has yet dared to re-introduce such a measure.

Life takes us all through dramatic ups and downs. We are all part intellects, but we are also human being with bodies and lives that need nourishment and strengthening. Watching the film, I believe that Aaron was so nourished by a loving family. They and the rest of the world grieve the loss of Aaron. We should pause to honor such families and homes that provide us with encouragement and resiliency. That’s what all of us need in the face of the sort of adversity that confronted Aaron Swartz.

Drew Clark is Publisher of BroadbandBreakfast.com and tracks the development of Gigabit Networks, broadband usage, the universal service fund, and wireless spectrum policy at http://twitter.com/broadbandcensus. Nationally recognized for his knowledge on telecommunications law and policy, Clark brings experts and practitioners together to advance the benefits provided by broadband: job creation, telemedicine, online learning, public safety, the smart grid, eGovernment, and family connectedness. Clark is also available on Google+ and Twitter.

Member discussion