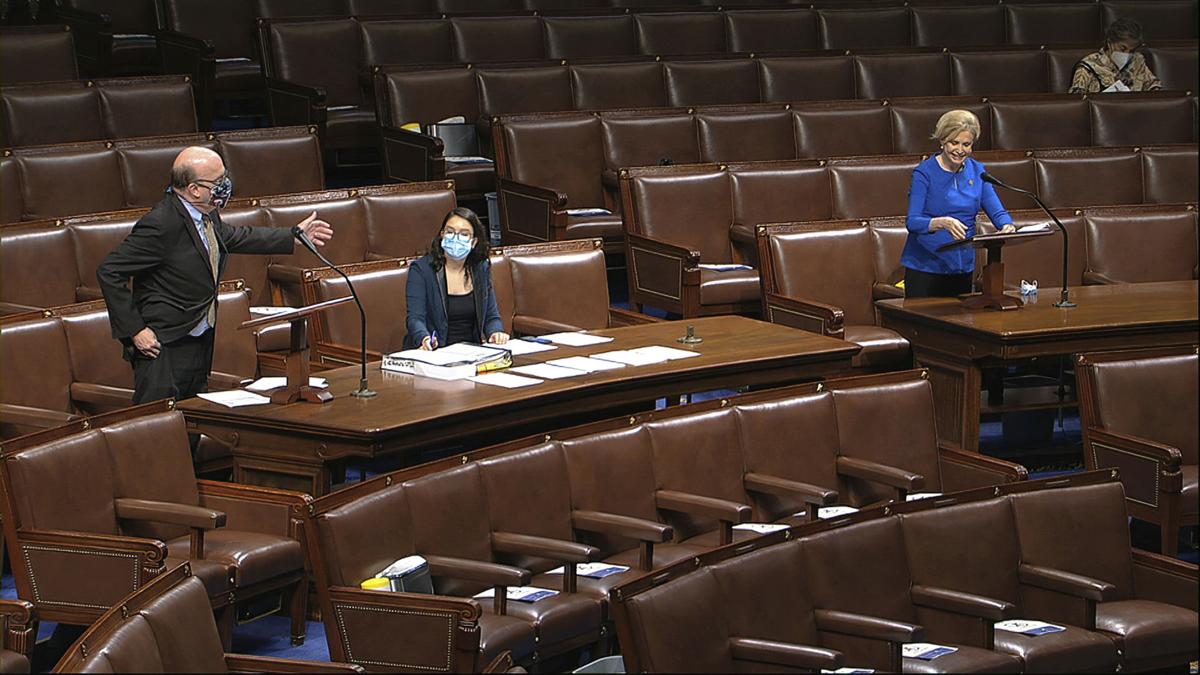

The House Meets to Debate Paycheck Protection Act Funds. But Why Can’t Congress Conduct Business Remotely?

April 23, 2020— Congress is “unwilling and unable, but mostly unwilling” to attempt remote voting, said Daniel Schuman, the policy director of Demand Progress, at a webinar hosted by the Cato Institute on Thursday. With congressmen spread across the country practicing social distancing, the answer t

April 23, 2020— Congress is “unwilling and unable, but mostly unwilling” to attempt remote voting, said Daniel Schuman, the policy director of Demand Progress, at a webinar hosted by the Cato Institute on Thursday.

With congressmen spread across the country practicing social distancing, the answer to the question of how they vote, pass laws, and help run the country has been elusive.

The question was in the air again on Thursday as members of Congress returned to Washington to debate and vote on the national legislature’s forth major coronavirus stimulus package – a $484 billion funding measure, with a $310 billion replenishment of funds for the Paycheck Protection Program. Other funding was for hospitals and COVID-19 testing.

The measure was the first time Congress has convened for traditional legislative debate since the passage of the U.S. CARES Act on March 27.

Congress passed the first coronavirus-focused measure on March 8, an $8.3 billion emergency spending bill. The second, which passed the House on March 12 and the Senate on March 18, spent about $500 billion on unemployment insurance.

The U.S. CARES Act was the third measure, and totaled more than $2 trillion. The package included $300 billion for the first round of the PPP, and which were already spent by last week.

The Paycheck Protection Program provides forgivable loans for businesses to retain their employees for 2.5 months.

During all of these legislative debates, once central question has been: Why can’t Congress conduct its business remotely?

Some claim that electronic voting is not safe enough, while others say that congressmen are too old to adapt to new technologies.

“The legislative branch, for the foreseeable future, is defunct,” said Schuman, an often-forthright critic of a highly inactive Congress.

Schuman dug into Congress’ unreadiness and reluctance to adapt.

“Congress historically is unwilling and unable to invest in itself,” he said. Apparently, several motions have been proposed in the past to create a nuclear-like contingency plan for electronic voting, but Congress has chosen not to pursue them.

He expressed his belief that congressmen have failed to act because they were afraid that their spending on electronic voting system would represent “frivolous spending” to their constituents. As a result, they use technology that Schuman described as “the oldest, jankiest stuff.”

Schuman contended that it would not be hard to implement an electronic voting system, but congressmen have a hard time “conceptualizing” that and furthermore don’t trust security.

Schuman contrasted these responses with the relative readiness of the U.K. parliamentary system, which recently announced that it will be conducting voting through Zoom. In addition, Schuman mentioned how New Jersey and Utah have adopted similar procedures for their state assemblies. “The problem isn’t the security but the people.”

Another problem of a lack of voting, besides a sluggish legislature, is that it cedes power to the executive branch, throwing the country’s system of checks and balances into disarray. “They are making the executive branch very powerful,” Schuman said, referring to the legislature’s relative absence from political affairs.

“This is really about political will. This is about the desire to do your job and to innovate,” Schuman said.