FCC Adopts Direct Final Rule Over Protests

'Certainly under this Chairman, it will not be abused,’ FCC's General Counsel vowed.

Cameron Marx

WASHINGTON, July 24, 2025 – The Federal Communications Commission voted 2-1 Thursday to give its bureaus explicit authority to use the direct final rulemaking process to eliminate regulations.

FCC Chairman Brendan Carr touted the passage of the item, though his initial statement only focused on the 11 regulations the FCC was eliminating this month as part of the order, and did not mention the delegated authority to the bureaus.

“Today’s action will remove 11 outdated and useless rule provisions – covering at least 39 regulatory burdens, 7,194 words, and 16 pages,” Carr said. “Say goodbye to restrictions on phone booth closures, captioning on analog TV receivers, auction obligations that lapsed 20 years ago, and references to long-repealed telegraph rules.”

When asked by Broadband Breakfast about the authority delegated to the bureaus, Carr explained that the FCC had made “a number of changes” to the Order since the initial proposal.

“We did make a number of changes in response to the record that was developed, for instance, we did not move forward with the idea of a bureau issuing an NPRM,” Carr said.

The FCC’s proposal initially drew pushback for allowing only a 10-day public comment period, much shorter than the standard recommended 30-day window, raising transparency concerns from some stakeholders.

“There was some concerns that were raised about 10 days not being enough, and we’ve made clear that 10 days is the window for the rules at issue here, it could be a different period of time in the future,” Carr said.

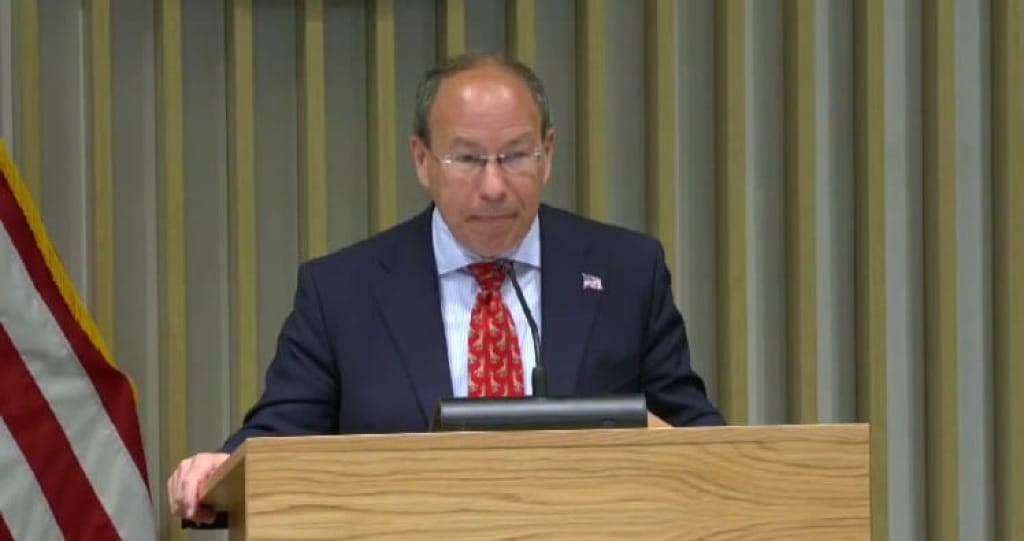

Adam Candeub, general counsel for the FCC, echoed Carr’s comments when asked about the 'direct final rule.'

“We just wanted to clarify that the bureaus for the most part had the power through order to eliminate rules that were exempt from the Administrative Procedure Act,” Candeub said.

“The APA has an exemption for rulemaking that is generally routine, insignificant in nature and impact, or inconsequential to the industry. So the bureaus always had that power to issue orders to eliminate those rules.”

“What we did here was simply clarify that and make that standardized throughout all the bureaus and offices,” Candeub said.

Candeub also argued that the new direct final rule would not be used by an FCC chair to bypass the possibility for judicial review when eliminating rules, a concern previously expressed by a consortium of 22 public interest groups.

“The power of the Commission to delegate matters to the bureaus and offices has existed as long as the Communications Act,” Candeub said. “This is not an issue that is specific to the direct final rulemaking. Furthermore, the direct final rule moves in the opposite direction, making clear that only for ministerial issues, which rulemaking is not required for, are dealt with on a bureau level… certainly under this chairman, it will not be abused.”

Those assurances were not enough for Democratic FCC Commissioner Anna Gomez, who voted against the order.

“This order does not limit the direct final rule process to elimination of rules that are objectively obsolete with a clear definition of how that will be applied, asserting instead authority to remove rules that are ‘outdated or unwarranted,’” Gomez said.

“It fails to meaningfully analyze the types of rules that could be eliminated through this process and then dismisses without explanation the minimum timeframe for public comment the Administrative Conference specifically recommended,” Gomez said.

Alisa Valentin, broadband policy director at Public Knowledge, one of the 22 public interest groups that raised concerns over the direct final rule, released a statement Thursday condemning the FCC’s adoption.

“The FCC’s adoption of a direct final rule procedure creates a dangerous path for bureaus empowered by Chair Brendan Carr to gut any rules it deems ‘obsolete, unlawful, anticompetitive, or otherwise no longer in the public interest,’” she said.

“With today’s action, the Commission could ram through substantive rule changes with virtually no oversight, which would shut out consumers, public interest organizations, researchers, technical experts, and industry’s ability to discover the proposed rule changes, much less respond effectively.”

Member discussion