Intervenors Accuse FCC of Exempting BEAD Recipients From Discrimination Rules

The FCC may have breached federal regulations by introducing a last-minute safe harbor in its recent digital discrimination policies.

Jericho Casper

WASHINGTON, May 2, 2024 – New federal digital discrimination rules need revision to remove an exemption excusing BEAD awardees from the regulations, creating imbalances never authorized by Congress, public interest groups allege.

These groups, including the Benton Institute for Broadband Society and Media Alliance, say the Federal Communications Commission erred by including a last-minute safe harbor provision in the rules for recipients of the $42.5 billion Broadband Equity, Access and Deployment program – without first seeking public input.

In their joint opening brief last week to the Eighth Circuit Court of Appeals, which is hearing a challenge to the new rules, the non-profit groups, also including Great Public Schools Now, claim the FCC violated the Administrative Procedure Act by failing to inform the public it was contemplating an exemption for BEAD awardees.

Excluding BEAD recipients from digital discrimination rules could impact users of broadband services provided by BEAD recipients, potentially leading to cases of differential treatment, as compared to users of services covered by digital discrimination rules.

Additionally, it will likely change market dynamics within the broadband industry by influencing competition, pricing strategies, and the overall landscape of broadband service offerings.

The safe harbor provision for recipients of BEAD came as a surprise to the intervenors in the case. According to the groups’ there was no presumptive BEAD safe harbor in the draft final rules that the commission published on October 25, but in the final order adopted November 15 the commission had included the following language:

“We adopt a presumption of compliance for policies and practices that are in compliance with specific program requirements for the Broadband Equity, Access and Deployment “BEAD” and Universal Service Fund “USF” high-cost programs. These programs exist to remedy current inequities in broadband deployment and are consistent with section 60506 and our rules adopted today to facilitate equal access to broadband internet service.”

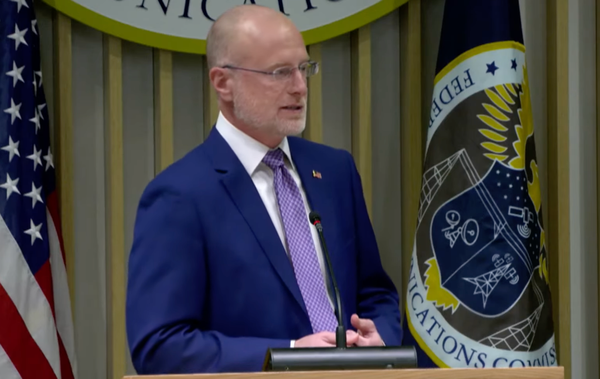

Starks said NTIA and industry associations asked for changes

Commissioner Geoffrey Starks later disclosed in a statement that these edits were requested by numerous industry associations, advocates, along with the BEAD program’s governing authority, the National Telecommunications and Information Administration.

“As it stands, the [digital discrimination] order now exempts the Biden Administration’s signature “Internet for all” initiative, BEAD, and the FCC’s own Universal Service Fund high-cost programs from these new rules through a presumption of compliance,” the filing states.

This inclusion, allegedly influenced by industry associations and advocates, has raised concerns about the order's impact on achieving equal access to broadband internet service.

The groups also filed for judicial review of the FCC’s choice to exclude complainants of digital discrimination from the right to file formal complaints, despite significant public comments on the issue. They questioned whether the FCC's actions were "arbitrary and capricious," given that the commission initially indicated it would not adopt such a presumption in its draft digital discrimination order.

As it stands, “Petitioners cannot file formal complaints on behalf of the communities they serve or seek full accountability against BEAD funding recipients if they engage in discrimination,” the groups’ brief states.

Throughout the notice and comment period, many organizations weighed in on whether individuals facing digital discrimination should be able to submit formal complaints in addition to informal ones. Formal complaints involve greater procedural rights than informal complaints, but often carry more legal weight and protection.

Public Knowledge engaged in multiple in-person meetings with FCC staff to advocate for a formal complaint process. The advocacy organization filed letters which noted that a formal complaint process was required by the plain language of section 60506 of the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act.

Formal versus informal complaints

However, when the FCC released its final order, it only authorized informal complaints, a decision criticized in the groups' brief for lacking substantial justification.

Formal complaints for public interest groups carry significant weight in terms of legitimacy and legal implications. Formal complaints may attract media attention, prompt discussions at higher levels, and potentially result in policy changes or organizational reforms. They can lead to formal investigations, hearings, or legal proceedings.

Crucially, they create a documented record of the issue and the steps taken to address it, which is crucial for tracking progress, holding accountable parties responsible, and providing evidence for further actions, including legal challenges or advocacy efforts.

The FCC said that an informal complaint process satisfied the requirements set out for the commission in IIJA, and that implementing a formal complaint process would have burdened the commission. The commission, however, has said its approach to combating digital discrimination might evolve, prompting a reconsideration of this matter down the line.

The intervening groups have requested a 20-minute slot to present their oral arguments during the hearing tentatively scheduled for late September.

If the court accepts these arguments, potential outcomes could include reversing the FCC's order or issuing an injunction to halt its implementation pending further legal review.

The FCC will file a consolidated brief in late June responding to arguments presented in the opening briefs of both intervenors and petitioners.

In the opening brief of the petitioners, 20 industry groups contended that the FCC's digital discrimination order signifies a significant broadening of its authority. The petitioners invoked the “major questions doctrine” to question whether the adoption of these new rules falls within the jurisdiction of the FCC.

Member discussion