Mike Rogers and Bruce Crawford: A Path Forward on Spectrum

The lower 3 GigaHertz (GHz) and 7-8 GHz bands are the best opportunities to close our nation’s spectrum gap.

Broadband Breakfast

For decades, the United States has enjoyed electromagnetic spectrum superiority over its competitors in all domains — both military (space, air, land, sea, cyber) and commercial. This superiority is important as it underpins both our economic prosperity and our national security.

But in recent years, other countries — including China — have grown more aggressive in their efforts to “win” global technology competition, especially as emerging spectrum-based technologies are poised to reinvigorate economies, retool militaries, and reshape the competitive landscape.

The United States is well positioned to win that competition, and we have before us an unprecedented opportunity to strengthen our global advantage. This opportunity involves doing something we do best, which is finding common ground on developing policy for the good of all versus the needs of one. By collaborating on policy changes and with accelerated and targeted focus from key stakeholders that include Congress, the current administration, the Department of Defense, and the public and private sectors, we can secure a spectrum future that enhances economic prosperity, accelerates the development of advanced technologies, and keeps us safe at home and abroad.

Nearly every modern military system — from airplanes to satellites, tanks, ships and radios — depends on spectrum to function. Similarly, nearly every aspect of the modern digital economy requires spectrum and the wireless connectivity it enables. Moreover, the lines between these two worlds are blurring. Our military’s ability to defend our homeland and support our allies is becoming more and more reliant on commercial technology — especially spectrum-based wireless technologies. Meanwhile, our economy is growing because of technological advances fueled by Defense-based innovations in industries like autonomous systems, advanced computing, artificial intelligence, machine learning, and next-generation 5G.

Both our military and commercial sectors need access to spectrum — but today our national spectrum policies are struggling to keep up with critical needs. As former senior Department of Defense officials, we strongly believe we need to find win-win opportunities that support both needs and that advance both our national security and our economy. We should reject efforts to optimize only one at the expense of the other. Although strategically important, these are not binary decisions.

Importantly, time is of the essence. Although the U.S. has been the established global leader in wireless, a new technology superpower — China — is emerging with astonishing speed. The Chinese government has been actively mobilizing to contest global leadership in next-generation 5G technologies and accumulate geopolitical power by doing so.

We must do more to defend our global leadership position in response to this threat. Left unchecked, China and others will be able to leverage its spectrum position to dictate technology choices, equipment options, and innovation throughout the world, particularly in developing countries. This dominance will help to enable not only economic and commercial advantage but also their strategic military advantage. It could have a direct and tangible impact on our ability to project power and protect our strategic interests around the world.

The United States can address this challenge in a manner that maintains our world leading spectrum position and makes our economy and our military stronger. A healthy balance of the right technologies and the right policies are keys to that success. Moreover, both the civilian and military sectors have a vested interest in supporting this effort.

We must commit to solving both sides of the problem: Economic and national security

First and foremost, we must commit to actually solving both sides of the problem. Economic prosperity is absolutely important but solutions must also support national security goals and objectives that include fully optimized and modern warfighting capabilities. We need the commercial sector and the U.S. Federal Communications Commission to provide a long-term spectrum plan with a defined set of spectrum auctions over the next decade. Too often our military is forced to respond to band-by-band spectrum access requests without any global view of the policy objective or insight into when or where the next request will be received. That is not how the military works, nor should it. The administration’s recent National Spectrum Strategy and Implementation Plan are a great start. Together, they set out a timeline for studying new bands for both military and commercial use. These are positive steps but we must now move quickly with decisive action on spectrum that delivers bold and innovative solutions.

Second, we need to find acceptable trade space that enables and incentivizes our military and commercial sectors to partner to identify the spectrum bands that the U.S. can best leverage to retain strategic advantage and support U.S. innovation.

Late last year, the administration identified the lower 3 GigaHertz (GHz) and 7-8 GHz bands as the best opportunities to close our nation’s spectrum gap. This spectrum aligns with our allies around the globe and should be our priority. We should explore all opportunities for full-power commercial access to these bands while ensuring that the needs of federal missions are fully met. We should always look to how we best modernize all our spectrum capabilities in the process.

Third, we should look for win-win opportunities. The commercial deployment of next-generation networks drives our economy and supports the complex and diverse missions of federal agencies, at home and abroad. The United States has a long history of modernizing the spectrum-related systems of federal agencies to better perform their missions while freeing up spectrum for auction. We should be willing to look for these win-win opportunities again, and we should not lock ourselves into options that do not consider how all users can be more efficient with more advanced systems.

Finally, we must be bold and audacious in accelerating the development of a technology-based solution. We are encouraged by recent policy recommendations, but policy solutions alone will not solve the entirety of the problem. We’ve overcome other science- and technology-based challenges, and we can do so here, too. Just three years ago, great minds came together in a short period of time with focused energy and resources to overcome another strategic challenge related to the global coronavirus pandemic. Similarly, both sides should work together here to drive advanced solutions to the problem of spectrum scarcity.

We agree with those who envision a future where dynamic spectrum sharing could someday support both military and full-power commercial needs. However, we are also realists, acknowledging that the current sharing technology has proven inadequate at accomplishing that goal. We must partner and invest in long-term sharing solutions while also recognizing the immediate generation of wireless technology will be built off well-tested sharing solutions that protect federal users while guaranteeing commercial power levels, access rights, and interference protection that facilitate the deployment of globally competitive, licensed, wide-area deployments.

Our national security and economic prosperity require domestic strength and wireless technological superiority that supports federal missions and commercial evolutions. Pursuing these kinds of opportunities will allow us to craft spectrum policy that achieves national security in the broader sense: that includes military power, but it also includes the security provided by a world leading technology base. It can be done.

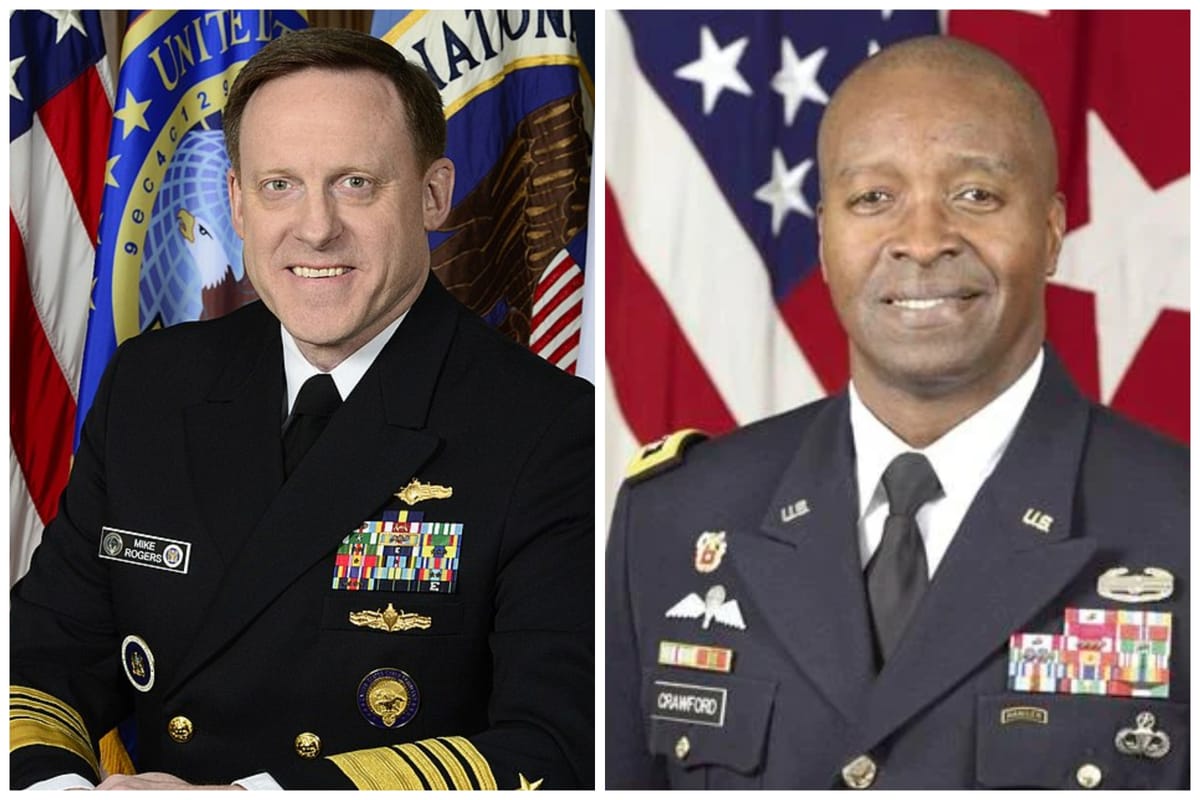

Mike Rogers, a retired U.S. Navy admiral, previously served as commander of U.S. Cyber Command and director of the National Security Agency.

Bruce Crawford, a retired lieutenant general, previously served as chief information officer of the U.S. Army.

This Expert Opinion was originally published in Stars & Stripes on March 20, 2024, and is reprinted with permission.

Broadband Breakfast accepts commentary from informed observers of the broadband scene. Please send pieces to commentary@breakfast.media. The views expressed in Expert Opinion pieces do not necessarily reflect the views of Broadband Breakfast and Breakfast Media LLC.