State Control Over FCC’s Pole Regulations – a Blessing or a Curse?

Twenty-three states choose to regulate their own pole attachment processes.

Jericho Casper

WASHINGTON, Oct. 30, 2024 – For nearly half of U.S. states, the push to expand broadband access comes with an added challenge: navigating a complex web of state-specific regulations governing utility poles.

Currently, 23 states and the District of Columbia have exercised "reverse preemption," choosing to regulate their own pole attachment processes rather than default to the Federal Communications Commission's standards under Section 224 of the Communications Act.

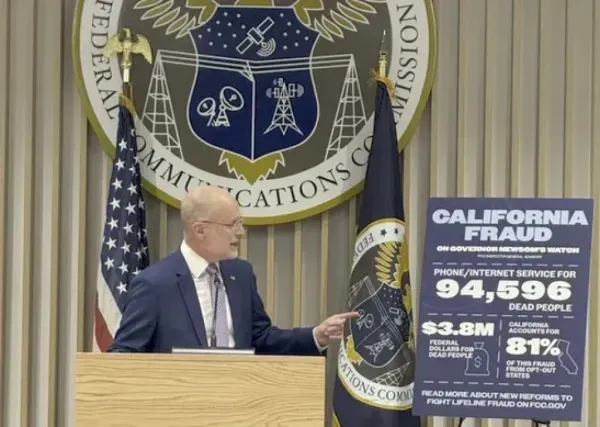

State utility commissioners discussed the pros and cons of this approach during a Federal Communications Bar Association panel Tuesday, noting that its success largely depended on each state’s ability to manage oversight effectively.

The practice of reverse preemption isn't a silver bullet, and it can introduce its own set of problems, particularly if states lack the resources or oversight structures to manage it effectively.

In Washington state, for instance, local control has exposed several regulatory gaps. The state's regulatory framework for pole attachments is split between investor-owned utilities (IOUs) overseen by the Washington Utilities and Transportation Commission (UTC) and Public Utility Districts (PUDs) that operate independently.

“A major issue that we find in Washington is the jurisdictional checker board. You'll find IOUs under the UTC jurisdiction. However, 50% of the state has electric service provided by either municipalities, co-ops or PUDs, which are exempted from UTC regulation,” said Mark Vasconi, president of Vasconi Consulting, and former director of the Washington State Broadband Office.

The split approach created other issues, Vasconi said.

“One of the issues has been that there's a lack of transparency with respect to poll pricing and poll policies on the part of PUDs. Where this really comes into play is in the development of BEAD, which has focused on rural parts of the state, where PUDs are the primary pole owners,” he said.

Massachusetts has faced similar issues with reverse preemption. One regional fiber provider, GoNetspeed, recently warned that current pole regulations could jeopardize $147 million in BEAD funding for the state. The company’s CEO told the FCC last week that pole attachment processes in Massachusetts can take up to four years, far longer than the 90 days typical in Connecticut.

Meanwhile, California stands out as a success story under reverse preemption. With its “one-touch make-ready” rules and mandatory database requirements for pole owners, California has managed to expedite attachment processes and enhance transparency.

“In California, we have an open proceeding…considering strategies for increased and non-discriminatory access to poles and conduit,” said Commissioner Darcie Houck of the California Public Utilities Commission. Of the state’s choice to adopt reverse preemption, Houck said, “it also allows us to promote robust competition for telecommunication services by streamlining access to utility poles.”

Still, she acknowledged the practice can have drawbacks, including the substantial resources required to manage and oversee these policies effectively.

Member discussion