The Google Book Search Settlement: Some Authors Still Fear It Robs Them of Power at the Bargaining Table

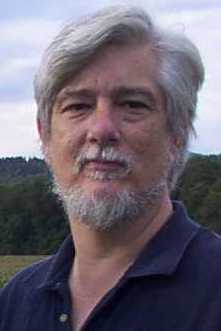

SAN FRANCISCO, May 10, 2010 – Science fiction author Michael Capobianco has spent much of his life writing about the futuristic subject of space exploration – nevertheless he’s not willing to become part of the new world that Google would create with its book search class- action lawsuit settlement

SAN FRANCISCO, May 10, 2010 – Science fiction author Michael Capobianco has spent much of his life writing about the futuristic subject of space exploration – nevertheless he’s not willing to become part of the new world that Google would create with its book search class- action lawsuit settlement agreement.

““Our primary objection to it is that it’s turning copyright on its head,” says Michael Capobianco, the author of five out-of-print science fiction books. “It’s creating a situation where authors must register to stop Google from doing what they’re going to do … it’ll be a really unfortunate turn of events if that kind of thinking ends up pervading our culture.”

“I’m waiting for the market to mature a bit,” says the author of five out-of-print science fiction books. “This is a priod of transition and it’s just the very beginning of the digital era for books.”

If a federal district court judge in New York approves of a proposed legal settlement between Google and two major U.S. authors’ and publishers’ groups, the search behemoth could become the world’s largest purveyor and custodian of digital books.

Google unveiled its plan to create an online database of “all the world’s books” in 2004. Publishers and authors sued, alleging that the scanning of their books infringed upon their copyrights. Google argued that its project was legal because it only made limited excerpts available to the public.

So far, Google has scanned more than 12 million books from the collections of various academic libraries both in the United States and abroad. As a point of comparison, the Library of Congress, founded in 1800, houses 32 million books.

Under the terms of the settlement, Capobianco would have received 63 percent of any of the revenues that Google would have made from having scanned his five out-of-print (but now digitized) books. Among other things, Google plans on selling subscriptions of its database to libraries, making copyrighted books available for purchase to consumers, and placing advertising against search result snippets of books. Capobianco wouldn’t have to share that revenue with publishers because he made sure that his rights reverted back to him after the books went out of print. (Google’s settlement provisions establishes revenue splits and procedures for authors who haven’t regained exclusive rights to their out-of-print books back from their publishers.)

Right now, anyone wanting to buy any of Capobianco’s books would have to find them second hand in a bookstore. That might change if Capobianco finds another publisher who wants to re-publish his work, or if he manages to publish his work as digital books through Amazon.com, of if he decides to sell them directly through his web site.

The point is, he wants to wait and be the one to decide where and how to publish, and on what terms. Years, ago, for example, he was able to land another publishing deal by agreeing to offer a series of books through a publisher. He was able to include a work that was previously published, but whose rights had reverted back to him. Google’s licenses are not exclusive, but Capobianco is still worried about how their availability as ebooks online might affect his ability to negotiate with publishers in the future. That’s why he has chosen not to participate in the settlement by opting-out. Capobianco is one out of 6,800 authors and their estates who have opted out of the settlement. Other big name authors who have opted out include Jeffrey Archer, Bret Easton Ellis and Ursula LeGuin, among others.

Capobianco is a vice-president of the 1,500-member group the Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers of America, which opposes the settlement — just as two other writers groups do. The groups want Google to obtain permission from individual authors and publishers first before making the books available to the public online. The groups fear that the settlement locks the writers into an agreement that they didn’t ask for, and most don’t understand, and that the settlement overrides the terms of their existing book contracts.

“Our primary objection to it is that it’s turning copyright on its head,” Capobianco says. “It’s creating a situation where authors must register to stop Google from doing what they’re going to do … it’ll be a really unfortunate turn of events if that kind of thinking ends up pervading our culture.”

Copabianco and other panelists will discuss the impact of the Google Book Search Settlement and its implications for the licensing of digital books Tuesday at the Intellectual Property Breakfast Club meeting in Washington, D.C.

Member discussion