The Rise, Reign, and Self-Repair of Zoom

May 8, 2020 – Eric Yuan came up with the idea for Zoom as a student while taking 10-hour train rides to visit his girlfriend in China. In 2011 he left Cisco Webex to found Zoom in San Jose, California, with the mission “to make video communications frictionless.” Zoom earned a billion-dollar valuati

David Jelke

May 8, 2020 – Eric Yuan came up with the idea for Zoom as a student while taking 10-hour train rides to visit his girlfriend in China. In 2011 he left Cisco Webex to found Zoom in San Jose, California, with the mission “to make video communications frictionless.” Zoom earned a billion-dollar valuation by 2017 and went public in 2019 in one of the most successful IPOs of that year.

And then the coronavirus appeared in Zoom’s waiting room, and it was not to be ejected from the chat.

As Americans have entered a world riddled with tele-prefixes, Zoom, whether it has wanted to or not, has entered the pantheon of Tide and Alexa to become a household name. By April 1, the number of Zoom’s daily participants skyrocketed from 10 million in 2019 to 200 million.

Indeed, Zoom became overnight king of an increasingly-important industry thrust into new prominence by the pandemic: Videoconferencing.

As hundreds of millions of Americans and billions of global citizens adjust to new norms for work, medicine, and education, Zoom has emerged as the go-to application, cutting commute times to zero.

What is Zoom and what propelled it to widespread name recognition? It’s not Webex

The most likely answer to what propelled Zoom to prominence comes from its mission statement— “to make video communications frictionless.”

Rachna Sizemore Heizer, a member at large of the Fairfax County Public Schools Board, highlighted simplicity as an advantage in her initial decision to use Zoom for her school board meetings. “It’s easier to understand if you’re new to the stuff,” Heizer said.

Cynthia Jelke, 18, a sophomore at Tufts University, found Zoom essential to her success. “I genuinely wouldn’t be able to do my education without it,” Jelke said.

Even the Federal Communications Commission, the agency tasked with improving communications, drew criticism on Tuesday for using Cisco Webex video conferencing technology to launch its Rural Digital Opportunity Fund auction webinar.

The web seminar designed to teach applicants how to apply for for more than $20 billion worth of funds ended up turning away business and media leaders due to a clunky audio-capacity limitations.

Commentators in the chat box complained in real time of the frustrations they faced. User “Natee” chirped at 4:10 p.m. on that webinar: “Webex is no good. That is why the original Webex developer created Zoom.”

Workplaces and schools have taken to Zoom

The workforce has also taken quickly to the interface. Patrick McGrath, a software engineer from Chicago, praised Zoom for its Whiteboarding feature, which allows users to sketch concepts in a creative and expressive way. “It allows for collaboration,” McGrath said in an interview with Broadband Breakfast.

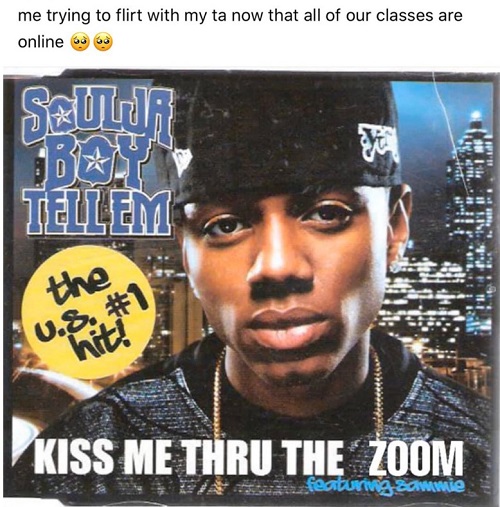

Then there are the memes. Perhaps because Zoom resonated with teenagers, many of whom have had to use Zoom for school, it has become an endless generator for viral content and a hub for consolidating a shared experience.

Students from different colleges started saying that they all attend “Zoom University.” Zoom University T-shirt vendors began popping up online.

Zoom has been an endless source of inspiration for meme artists

Zoom also offers the option to easily customize one’s background without a green screen, adding a touch of personalization that is reminiscent of social media.

The videoconferencing service has a “hotter brand” than other teleconferencing companies, Rishi Jaluria, a senior research analyst at D.A. Davidson told The New York Times. “Younger people don’t want to use the older technology.”

Joshua Rush, 18, a high school senior in Los Angeles, told the Times: “Out of nowhere, I feel like Zoom has clout.”

The memes “help lighten to mood of being kicked out of your school,” Tufts sophomore Jelke told Broadband Breakfast.

If there was any doubt that Zoom had chiseled a frieze in the pantheon of pop culture, Saturday Night Live’s first virtual episode put that skepticism to rest.

“Live from Zoom, it’s Saturday Night Live,” announced the cast of SNL, who used Zoom for large swaths of its episode on April 11.

Tom Hanks, the host of the episode and a popular coronavirus survivor, had fun with the monologue, using video cuts and costumes to play different characters. The episode featured many playful jabs at the ubiquitous platform, and one sketch dedicated to Zoom profiled common videoconferencing personalities.

OK, so why is Zoom suffering?

Zoom Sales Leader Colby Nish with company logo in the back: “Delivering happiness”

Almost as quickly as “Zoom” has become a verb, “Zoombombing” has entered the national lexicon. Zoombombing occurs when a Zoom meeting host or attendee leaves the join URL unattended, which, in the world of the internet, can happen many different ways.

A prankster can then use this neglected link to crash a meeting and broadcast improper material, such as pornography or racist content. The FBI issued a warning about Zoombombing on March 30 — but that hasn’t curbed the rise of this new breed of troll.

#FBI warns of Teleconferencing and Online Classroom Hijacking during #COVID19 pandemic. Find out how to report and protect against teleconference hijacking threats here: https://t.co/jmMxyZZqMv pic.twitter.com/Y3h9bVZG30

— FBI Boston (@FBIBoston) March 30, 2020

The Anti-Defamation League has already documented 21 instances (as of April 6) of anti-Semitic Zoombombing at the levels of government, school and worship.

Journalists Kara Swisher of The New York Times and Jessica Lenin of The Information were forced to shut down their Zoom webinar on feminism in tech on March 15, when trolls broke into their meeting and began broadcasting a shock video. A meeting of the Indiana Election Commission was interrupted by a video of a man masturbating.

The graphic examples don’t stop there:

Okay so someone started screensharing extremely graphic porn during the Lauv and Chipotle + Zoom hangout and it abruptly ended lol. Maybe these platforms need to be thoroughly tested first?

*blurred for obvious reasons* pic.twitter.com/9mBlQSia1U

— Kenneth Takanami (@exitpost) March 17, 2020

When McGrath, the software engineer from Chicago, discussed the issue of security, he responded “we have a definite team to take care of that… It’s totally because of the security concerns that have been going around.”

From Zoombombing to… other privacy and security concerns

Then there’s the issue of privacy.

As early as March 26, Vice reported that it had uncovered that Zoom had been sharing its users’ data with Facebook without their knowledge.

Data being shared included when the user opens the app, details on the user’s device such as the model, the time zone and city the user is connecting from, which phone carrier the user is using, and information that allows third-party companies to target a user with advertisements.

“That’s shocking. There is nothing in the privacy policy that addresses that,” Pat Walshe, an activist from Privacy Matters who has analyzed Zoom’s privacy policy, said in a Twitter direct message with Vice.

And then there’s the issue of the Chinese server.

The University of Toronto’s Citizen Lab published a report showing that some Zoom user data is accessible by the company’s server in China, “even when all meeting participants, and the Zoom subscriber’s company, are outside of China,” the authors of the report wrote.

The Toronto lab also noted that Zoom’s arrangement of owning three Chinese-based companies and employing 700 Chinese mainland software developers “may make Zoom responsive to pressure from Chinese authorities.” These vulnerabilities give the Chinese government a way to tap in to Zoom phone calls said Bill Marczak, a research fellow at Citizen Lab.

Zoom’s claim to offer end-to-end encryption was scrutinized by The Intercept and found to be wrong. The company was forced to backtrack and apologize in a blog post by Oded Gal, Zoom’s chief product officer:

“In light of recent interest in our encryption practices, we want to start by apologizing for the confusion we have caused by incorrectly suggesting that Zoom meetings were capable of using end-to-end encryption…. While we never intended to deceive any of our customers, we recognize that there is a discrepancy between the commonly accepted definition of end-to-end encryption and how we were using it. This blog is intended to rectify that discrepancy and clarify exactly how we encrypt the content that moves across our network.”

The Attorney General of New York sent a letter to the company asking questions regarding its privacy shortcomings that allow Zoombombing and questioned its murky agreement with Facebook. That was just one of 26 letters the Zoom office has received from state attorney generals.

The problems keep coming. Some entities are dropping Zoom. Elon Musk banned SpaceX from using Zoom. Taiwan has banned it. Germany has restricted its usage.

A shareholder for Zoom is suing the company for overstating its encryption capabilities. Even local school districts, such as the Fairfax County Public Schools, have deemed the technology unsafe, and are experimenting with alternatives.

The Era of Self-Repair

Days after Vice’s report, Zoom changed codes that had shared user data with Facebook.

Zoom began allowing users to deactivate the Chinese server. By April 25, any user that had not expressly kept their data on the Chinese server was to be automatically removed from its data route.

Such an “opt-in” approach to data sharing is rare in the world of privacy.

And Zoom has been highly communicative about its blunders. Yuan has posted blogs repeatedly on his website updating users about security and new, common-sense features such as making security settings more prominent and reporting users.

He has also used his blogs to draw attention to the tools that have always existed for dealing with trolls, such as good cyber hygiene and tutorials for using the Zoom Waiting Room to vet join requests.

You can ask Zoom anything, as long as it’s on Zoom

Most notably, Zoom is hosting a series of weekly webinars since April 8 with Yuan himself, called “Ask Eric Anything.” He’s made himself as available as a CEO can be.

At one of the first of these webcasts, the majority of questions revolved around interface and troubleshooting, but some addressed security concerns.

For “the next 90 days,” Zoom will be “incredibly focused on enhancing our privacy and security,” promised Yuan.

See “Zoom CEO Eric Yuan Pledges to Address Security Shortcomings in ‘The Next 90 Days’,” Broadband Breakfast, April 20, 2020.

In fact, Zoom has branded itself around “The Next 90 Days,” where it has committed to focusing itself on solely privacy-related challenges.

Asked about the specifics of its efforts by Broadband Breakfast, a Zoom spokesperson said, “Together, I have no doubt we will make Zoom synonymous with safety and security.”

Zoom’s has also had a slew of conspicuous hires: Katie Moussouris, a cybersecurity expert who debugged Microsoft and the Pentagon; Leah Kissner, Google’s former head of privacy; and Alex Stamos, director of the Stanford Internet Observatory and Facebook’s former chief security officer.

During Stamos’ time at Facebook, he advocated greater disclosure around Russian interference on Facebook during the 2016 election. His insistence that Facebook do more created internal disagreements that eventually led to his departure.

“To successfully scale a video-heavy platform to such a size, with no appreciable downtime and in the space of weeks,” Stamos said in a blog post explaining his decision to temporarily leave Stanford and join Zoom, “is literally unprecedented in the history of the internet.”

He described the challenge as “too interesting to pass up.”

In the end, the problem that Zoom has faced isn’t specific to Zoom, but a human problem. The real challenge, as Stamos said, “is how to empower one’s customers without empowering those who wish to abuse them.”

Member discussion