American AI in a Changing World: Experts Debate Sovereignty, Strategy and Global Stakes

The discussion focused on governments shifting from regulating AI to actively participating in its markets

Naomi Jindra

WASHINGTON, Oct. 21, 2025 – Global leaders are racing to invest in and regulate artificial intelligence, creating new questions about “sovereign AI” and how much control governments can or should exert over the technology.

Today at a Brookings Institution panel discussion titled “American AI in a Changing World,” experts from the United States, Europe and Canada discussed how national strategies are taking shape and where cooperation and competition intersect.

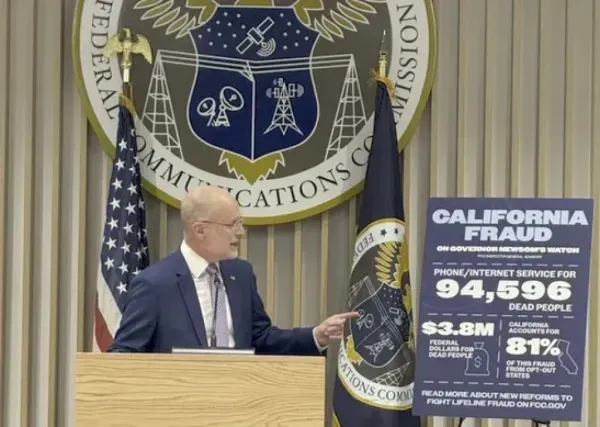

Joshua P. Meltzer, a senior fellow at Brookings, opened the panel by noting the scale of global investment. “In 2024 private sector investment was over $100 billion into AI,” he said. “That’s 12 times private sector investment into China in that year.” He added that the tension between innovation and regulation has defined AI policy worldwide.

AI sovereignty refers to a government’s effort to control and derive national value from artificial intelligence systems, rather than depend entirely on foreign companies or infrastructure.

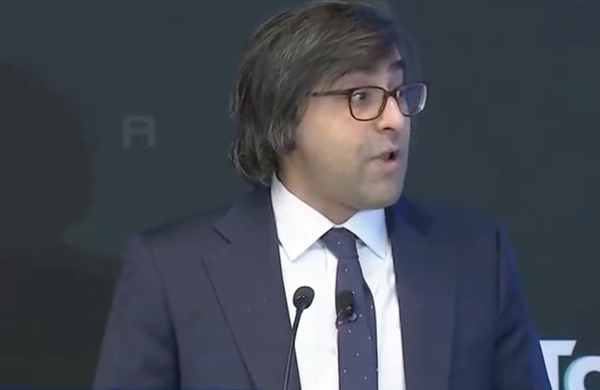

“Fundamentally, as I mentioned, you know, it’s an industrial policy with governments, typically national governments, putting the development, the deployment, and ultimately, the control of AI, and the kind of means of production of AI in the hands of domestic actors,” said Pablo Chavez, Founder and Principal at Tech Policy Solutions LLC and an Adjunct Senior Fellow at the Center for a New American Security.

Marc-Etienne Ouimette, founder of Cardinal Policy and a member of Canada’s National AI Task Force, said his team explored how to create “sovereign AI infrastructure” that builds domestic value while recognizing limits.

“It’s not about having complete control and complete domestic production ability over the stack, I don't think that is a reasonable expectation,” he said. “It’s looking at areas where you can maximize the areas where you have control.”

Ouimette pointed to energy supply, critical minerals and open-source architectures as key strategic levers.

“If different approaches pan out to developing new models that don’t essentially rely on pure scaling laws, that may actually equalize the playing board,” he said.

Samm Sacks, a senior fellow at Yale Law School’s Paul Tsai China Center, compared China’s AI strategy to that of the U.S., saying the two countries released “dueling AI action plans within three days of each other.”

“In both countries, there is debate about this concept of managed interdependence,” she said. “Beijing was able to capture a rhetoric win, by positioning itself as an inclusive, multilateral leader seeking to build a sort of AI for the developed world at a moment when the U.S. AI Action Plan was coming at it from a position of dominance.”

Sacks warned that developing countries do not want to be “a pawn in the U.S.-China great power competition,” and added that the U.S. must find ways to promote openness and democratic values while avoiding overreach.

Paul Timmers, a professor at KU Leuven and former director at the European Commission, framed Europe’s AI policy within a broader concern about sovereignty.

“Europe feels that there are these threats to its sovereignty, in the sense of being able to decide and act on [its] own future,” Timmers said. “We have had that at the time with the Chinese Huawei systems […] but nowadays, there’s a lot of concern about the cloud providers, the American cloud providers.”

He said Europe’s digital sovereignty push spanned from chips to networks to AI. “The position of Europe is not very strong, because about 80% of all ICT digital stuff used in Europe is bought from third countries,” he added.

Timmers cautioned against coercive “conditionality” in technology partnerships. “Respect for sovereignty could be the more commonly shared type,” he said. “Transactionalism […] is not very helpful for collaboration in the field of AI.”

Member discussion