If Trump Won, What Would Carr Do as FCC Chairman?

The agency's senior Republican outlined policy priorities in his Project 2025 chapter.

Jake Neenan

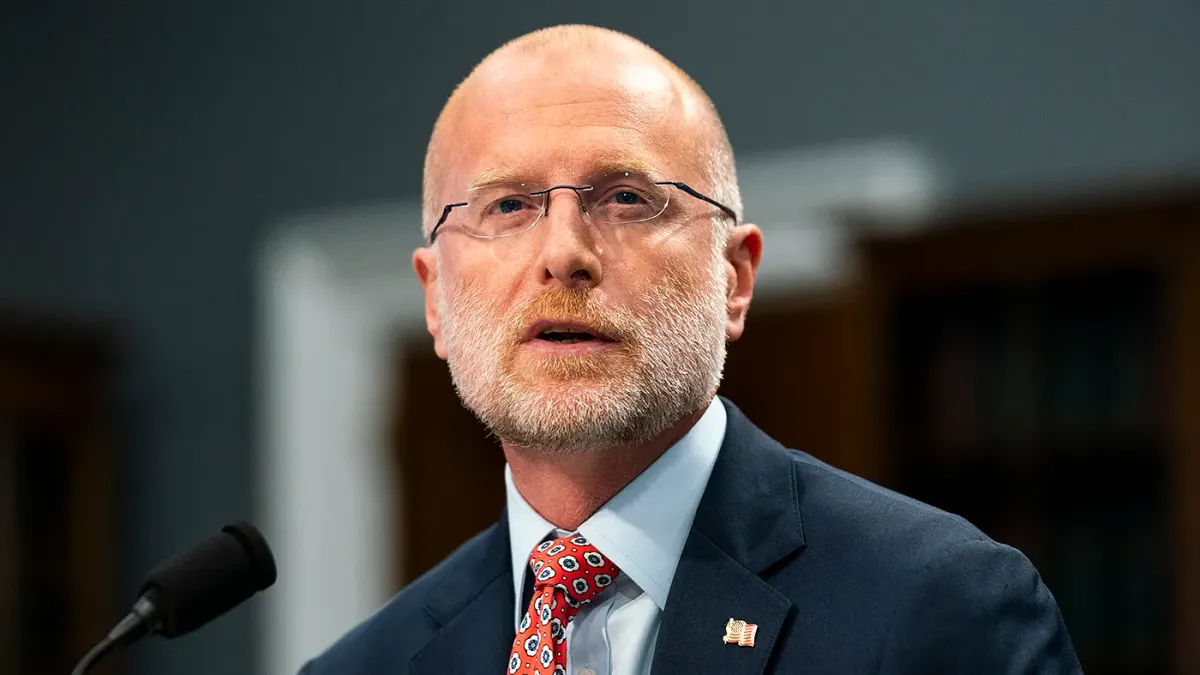

WASHINGTON, Oct. 29, 2024 – Some see FCC Commissioner Brendan Carr, the agency’s senior Republican, as the most likely candidate for chairman of the agency under a second Trump presidency. What would he do if Trump won, and if Carr were selected for the job?

Carr actually outlined his priorities for broadband and telecommunications policy in a chapter of the Heritage Foundation’s Project 2025 policy agenda. The widely available document has been highly criticized by opponents of former President Donald Trump during the presidential campaign: Trump and his campaign have disavowed it.

“The FCC’s prior reforms focused on streamlining the rules for small wireless facilities,” Carr wrote of broadband deployment. “The FCC should now explore similar action for the deployment of other wired infrastructure by imposing limits on the fees that local and state governments can charge for reviewing those wireline applications and time restrictions on the government’s decision-making process.”

Broadband BreakfastBroadband Breakfast

Broadband BreakfastBroadband Breakfast

New broadband deployment rules

Both parties at the FCC have sought to ease Internet Service Provider access to utility poles and speed up that permitting process, but the changes to local government approvals would be a departure from the current FCC.

In 2020, the Republican-led FCC clarified a previous order that required municipal governments to approve less substantial requests to modify wireless towers.

Now-Chairwoman Jessica Rosenworcel and Democratic Commissioner Geoffrey Starks dissented from the decision, arguing the agency should have sought input from local governments before the move. A group of 780 local and municipal governments took the agency to court over the order, but judges largely upheld the rules.

Chinese companies on the ‘covered entities’ list

Carr advocated for the agency to more regularly update its covered list, which includes Chinese companies deemed to be security threats by lawmakers. Inclusion on the list blocks a company from selling new products and network equipment in the U.S.

)He also proposed blocking ISPs from interconnecting at all with covered entities in an effort to prevent them from operating on an unregulated basis. Hawkishness on Chinese companies is an issue on which there’s bipartisan agreement.

The FCC added a company’s software products to the list over the summer and Rosenworcel and Carr partnered on a proposal to block covered companies from operating FCC technical certification labs.

But Carr’s proposals go a bit further than what the agency has done so far.

Carr also continued in the chapter to call TikTok, the short-form video service owned by the Chinese company ByteDance, a “serious and unacceptable risk to America’s national security” and said a conservative president should ban the social media app.

The FCC couldn’t itself take action there. Carr has maintained his anti-TikTok position even as Trump reversed course earlier this year and opposed banning the app.

Broadband BreakfastBroadband Breakfast

Broadband BreakfastBroadband Breakfast

But in another point of agreement with Rosenworcel, Carr also reiterated calls for Congress to fully fund its “rip and replace” program, which reimburses broadband providers for swapping out Chinese network gear.

Providers receiving FCC subsidy support are required to do so, but the program is facing a $3 billion shortfall that has left much of the work in limbo as smaller providers wait for funding.

Universal service and big tech

In the chapter, Carr urged Congress to tap big tech companies for Universal Service Fund contributions. The roughly $8 billion-per-year broadband subsidy is funded by fees on interstate voice revenue, a shrinking pool of cash that lawmakers in both parties consider in need of an update.

Rosenworcel told lawmakers working on legislation that would modernize the fund that she was wary of adding tech companies to the contribution base, fearing they would, like telecom providers, pass the fee on to consumers. She said online advertisers might be a safer bet, with a sizeable revenue pool but fewer pathways for consumer bills to go up.

Carr also said the agency should issue an order reinterpreting Section 230 of the Communications Act in a way that “will appropriately limit the number of cases in which a platform can censor with the benefit of Section 230’s protections.”

Blair Levin, a former FCC chief of staff and current senior analyst at New Street Research, wrote in an investor note after Project 2025 was published that he was skeptical courts would greenlight such a move. “Section 230 does not provide for any agency action,” he noted, and the conservative majority on the Supreme Court has made a point of curtailing federal agency authority.

Major FCC rulemakings

Carr wrote in the Project 2025 chapter that “The FCC should engage in a serious top-to-bottom review of its regulations and take steps to rescind any that are overly cumbersome or outdated,” but did not specifically mention the agency’s net neutrality or digital discrimination rules.

The former aimed to reclassify broadband providers as common carriers under the Communications Act, and the latter prevented ISP business practices that result in gaps in broadband access for low-income people and racial minorities.

He has made clear in public statements, though, that he opposes them.

“As he has attacked both for suppressing investment, investors can safely assume he will have the FCC proceed to reverse or weaken those rules,” Levin wrote at the time.

Both rulemakings were challenged in court by the telecom industry. Oral arguments took place last month in the digital discrimination case and they’re scheduled in the net neutrality case on Thursday, Oct. 31.

Carr has also publicly opposed the agency’s proposal to require AI-generated content labels on broadcast political ads and its proposed inquiry into bulk billing.

He dissented when the FCC moved forward with its $9 billion 5G Fund, arguing that the agency should have waited until the Commerce Department’s BEAD program was finished. The FCC is planning a reverse auction for the 5G Fund, but didn’t specify a date.

LEO broadband and Elon Musk

Elon Musk, the owner of satellite broadband provider SpaceX, has an ally in Carr.

He dissented when the FCC reaffirmed its denial of SpaceX’s application for rural broadband subsidies from the agency, alleging that Musk was being unfairly treated for posting right-wing political content on X, the social media platform he also owns. The agency has maintained that allegation is “not fact-based and wrong.”

Carr also offered to fly to Brazil and negotiate on Musk’s behalf when the country’s telecom regulator banned X after it refused to shut down accounts the government accused of spreading election misinformation.

Carr told Politico in early October that he wasn’t showing Musk special favor, but wants the FCC and government generally to promote the growth of satellite broadband. He said some of his references to SpaceX’s Starlink service are a shorthand for the technology generally, as Starlink’s 6,500 satellite constellation dominates the market.

“The FCC should expedite its work to support this new technology by acting more quickly in its review and approval of applications to launch new satellites,” he wrote in the Project 2025 chapter.

Levin wrote that Musk would likely be in for a friendlier FCC even if Carr weren’t ultimately the chair. The billionaire has become influential in Republican politics, actively campaigning with Donald Trump and offering a cash sweepstakes for registered voters who sign a petition in swing states – something the DOJ has warned could run afoul of election laws.

SpaceX is involved in spectrum disputes at the agency, including trying to block Dish from using its 12 GHz holdings for terrestrial broadband service and seeking a waiver of some interference rules to provide satellite cell service with T-Mobile, something both Verizon and AT&T have pushed back on.

SpaceX’s odds of getting its way would likely be greater – although not completely certain in every instance – under a Trump FCC, Levin wrote.

Member discussion